Background + Art Schools in 19th century

As we learnt earlier in the Course, 19th century colonial cities such as Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay saw the emergence of western style art schools. The existing Indian model of studying art had been built on a system of apprenticeship in parallel to the guru-shishya tradition of lineage in Indian religions and spiritual systems. This involved students learning from teachers to whom they were fully devoted.

The guru-shishya tradition was soon replaced by a British model of education which intended to offer practical knowledge to students, privileging Western aesthetics and the medium of oil painting. This change had a lasting impact on the preferred styles and subjects of Indian art.

Shift in Mediums

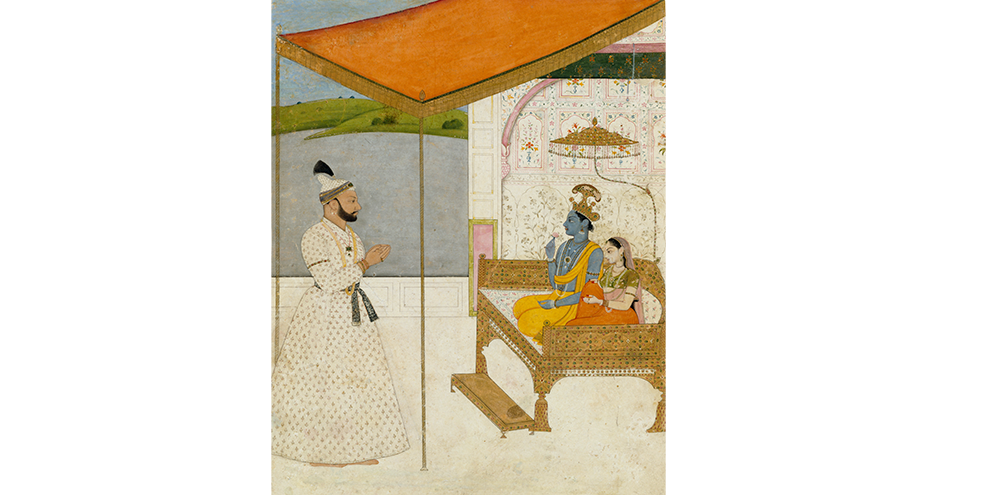

Oil on canvas paintings, particularly portraiture, connoted affluence and began to make their way into wealthy Indian homes, initially to impress Europeans. This marked a significant change from the taste for Mughal and Rajput paintings that had taken a hold of Indian artistic imagination for the past century. This moment coincided with major changes in artistic patronage, and declining support from Indian rulers and aristocrats that had long been the prevailing model. This was challenging for traditional artists as they lost the security of aristocratic patronage.

Shift in Patronage

Additionally, Salon art or Academic Naturalism, which showed human subjects in natural or social settings, began to take hold across India, especially by the 1870s. British officers had began to explore and collect Indian art, and art societies and exhibitions gave salon artists the opportunities to show and sell their works to a broader public in Indian cities. This paralleled developments all around the world, as artists began to depend much more heavily on showing their work in exhibitions in order to sell. In India, art societies modeled on the British Royal Academy facilitated this shift.

Individual Artistic Growth: Raja Ravi Varma

These developments in turn opened up new possibilities for artists in India to evolve and professionalise themselves as individuals, as opposed to the former guild or guru-shishya model.

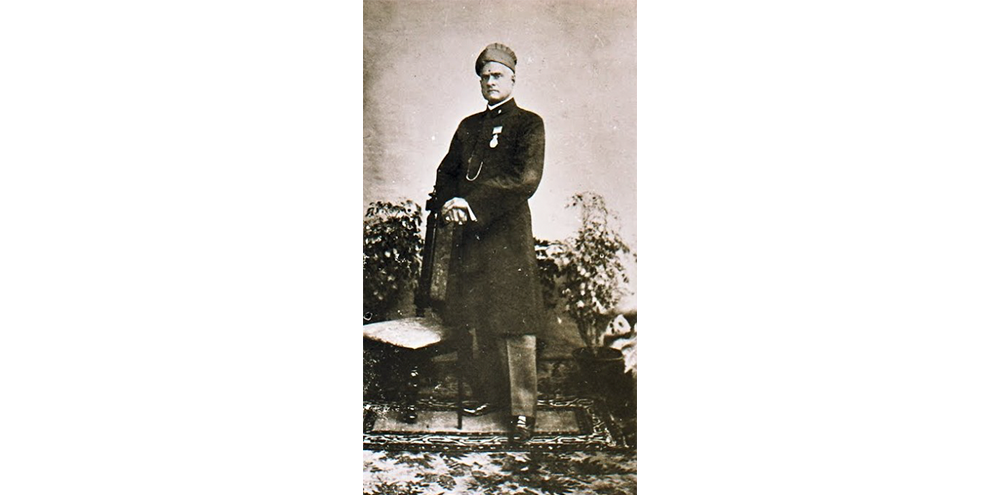

Raja Ravi Varma embodied this trend through his realistic oil paintings modeled on a European technique of illusionism. Despite several key paradoxes in his art and identity, particularly that he exemplified the stature of an academic artist without having ever gone to art school, he created the model of artist as entrepreneur in India. Ravi Varma was celebrated by the British and popular among Indians, with an appreciation for his work ranging from maharajas to broader society. Oleographs of goddesses and mythological narratives produced in his print studio were found in homes across the subcontinent, as the taste for Western art connoted status and refinement at the end of the nineteenth century. However, near the end of his life and career, his reputation suddenly plummeted and his work was criticized for not being spiritual or “possessing dignity.” This coincided with a rise of nationalism and a desire for a more authentic “Indian art.”

Despite these major developments in India’s artistic practice in the 19th century, Indian artists aspired to work towards a tradition that inculcated parts of their heritage. These were propagated by certain artists in the Bengal school of art which we shall focus on next.

Making of an ‘Indian style’ of painting

The beginnings of an “Indian style” of painting at the turn of the 20th century can be traced to artist Abanindranath Tagore and Ernest Binfield Havell, the superintendent of the Government School of Art in Calcutta from 1896 to 1905. Under Havell’s influence, Abanindranath rejected oil painting and realism which were the predominant forms of painting at the time. Instead, he began incorporating Indian themes and traditions into his work.

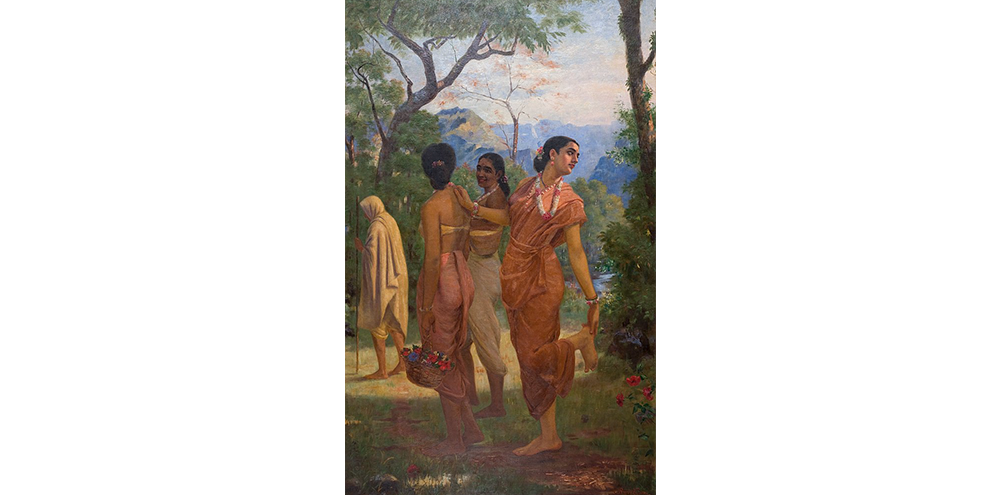

Krishna Lila

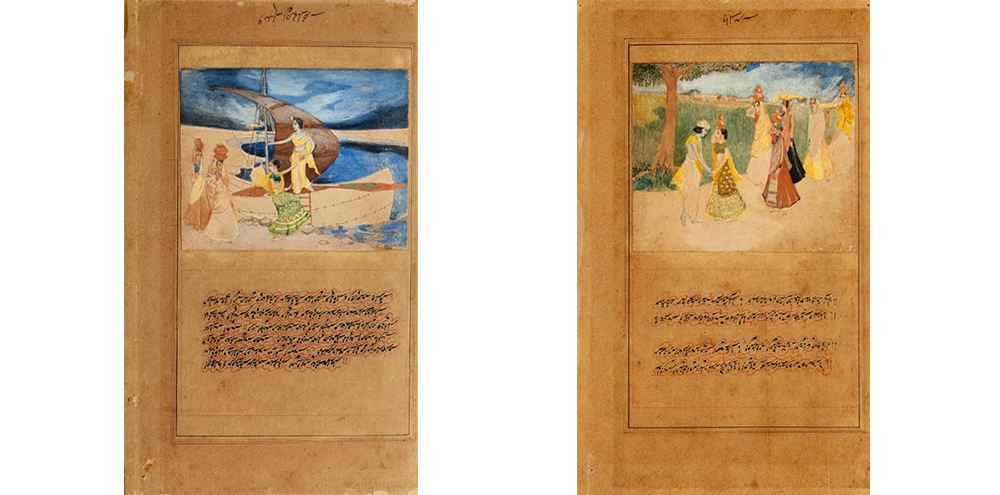

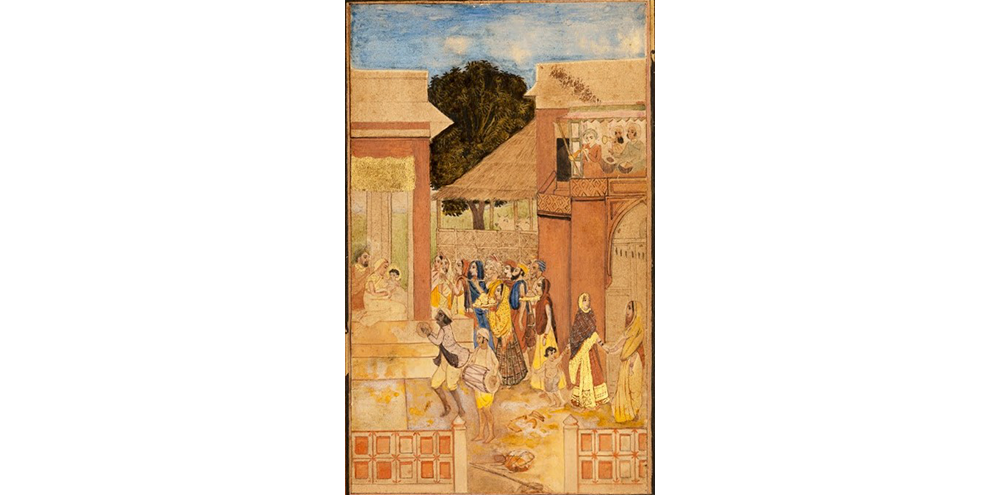

Abanindranath’s Krishna Lila paintings are some of his first attempts at this approach to bridge different traditions of Indian art. The Birth of Krishna (1897) employs a few devices from Mughal painting, like intricate borders, calligraphic text, a dense application of colours, and use of gold leaf. At the same time, both the subject and composition of the painting were inspired by Rajput court paintings. In this way, Abanindranath created a new space for indigenism and Indian art that addressed.

“the contours of a new heterogeneity, a new cultural space, growing out of cultural cross-connections beginning to emerge from this eclectic conundrum.”

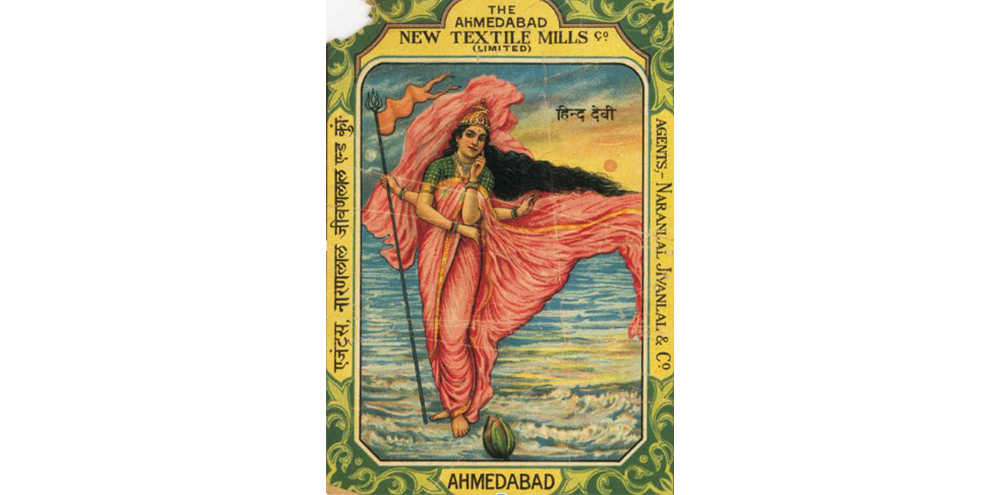

Bharat Mata

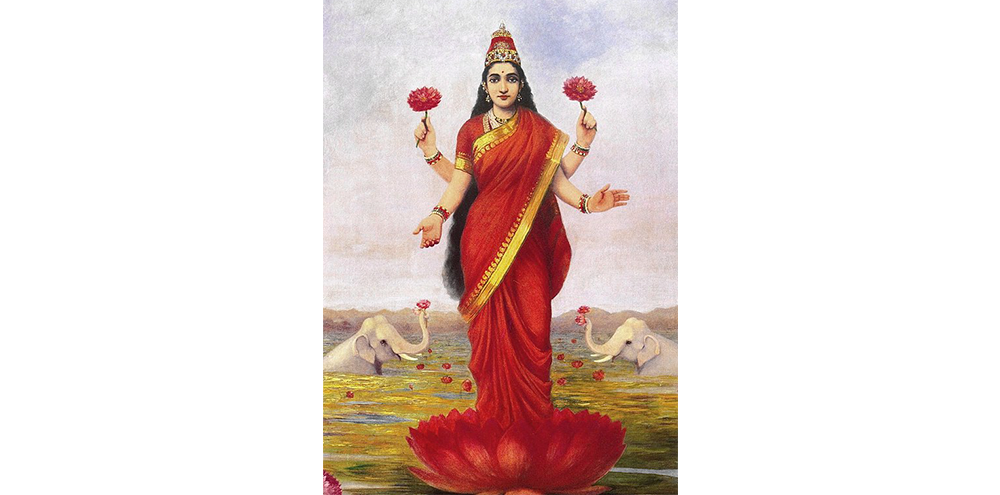

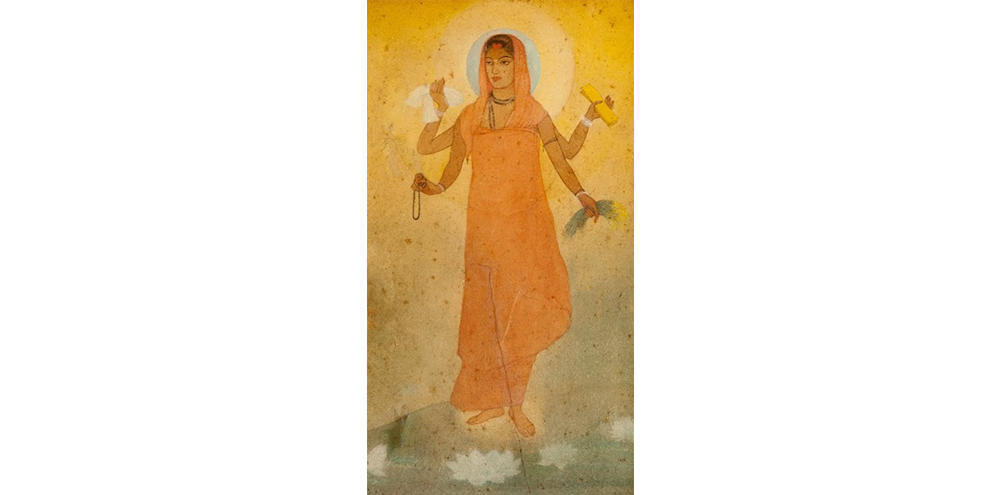

Abanindranath’s most famous painting, Bharat Mata (1905), is even bolder than his earlier work in its assertion of a new Indian identity and aesthetics through association with a hybrid art historical past. The idea of Bharat (India) as “Mother” began to take hold in popular culture across the subcontinent in the late 19th century, but Abanindranath’s painting may have been the first artwork to give an image to this idea. The painting, which you can see here, shows a four armed ascetic woman wearing a saffron sari and holding a rosary, piece of white cloth, manuscript, and tufts of paddy. The objects she is carrying can be seen as “attributes” or emblems of nationalist aspiration, namely food, clothing, learning, and spiritual knowledge.

Abanindranath painted Bharat Mata after the partition of Bengal in 1905, and the work became an iconic image of what was known as the Swadeshi (“of our own country”) Movement. This paralleled the movement for swaraj, or self-rule, and artists were encouraged to consider their work as a tool in the fight against the colonial rule. Interestingly, (Abanindranath had originally thought of her as Bangamata, Mother Bengal, but changed its title in support of the nation).

It is significant that this work – as a symbol of India – uses elements of Mughal painting and a wash technique inspired by Japanese art. Swadeshi art looked to visual sources from across Indian history — spanning Ajanta to Mughal painting, as well as to East Asia, as part of a broader movement towards Pan-Asianism inspired by dialogues between key cultural figures especially in India and Japan. Swadeshi condemned “foreign art,” which included Ravi Varma and colonial art schools, as well as early Buddhist art from Gandhara, with its Greco-Roman aesthetics and West Asian roots. (819). The return to traditional Indian art was a direct result of anti-colonial factions that were developing across the country through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These sentiments among artists and thinkers led to many new forms of artistic expression and thinking.