An Internationalist Vision: Rabindranath Tagore’s Shantiniketan

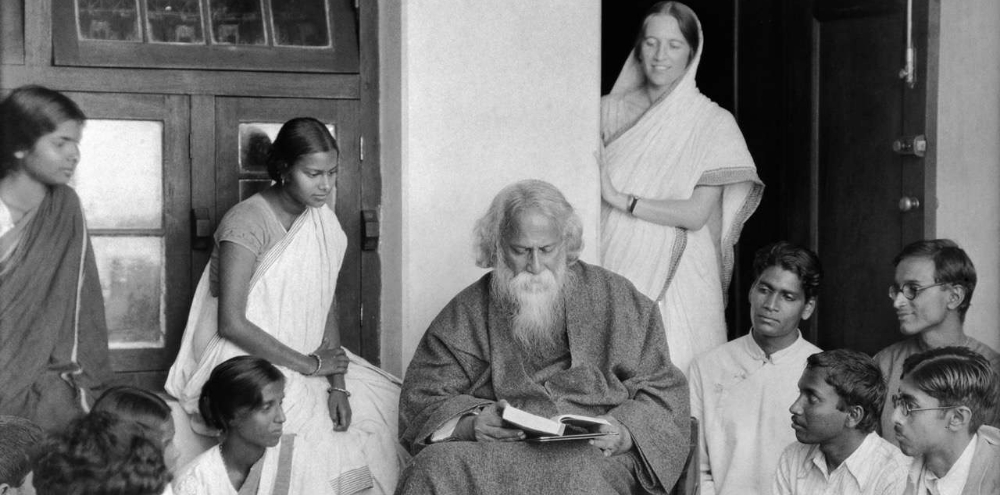

In Calcutta (now Kolkata), Abanindranath Tagore (1871—1951) and other figures associated with the Swadeshi movement rejected European academic art. Yet, 150 kilometres north, at Shantiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore (Abanindranath’s uncle) had begun an experimental and radical approach to art and education. Though he is best known as a poet and writer, Rabindranath (1861—1941) was a polymath and a complex figure. He was critical of any form of nationalism, including the progressive approach to nation-building that Swadeshi embodied as part of the freedom movement. Instead, he endeavoured to shape a democratic and equal vision founded on international and cross-cultural exchange in his own creative work and at the institution he built.

The Foundations of Shantiniketan

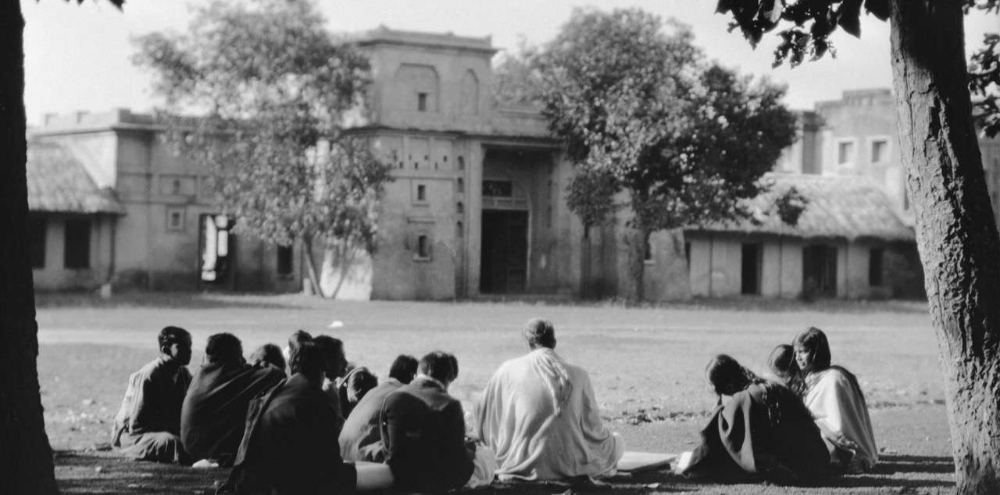

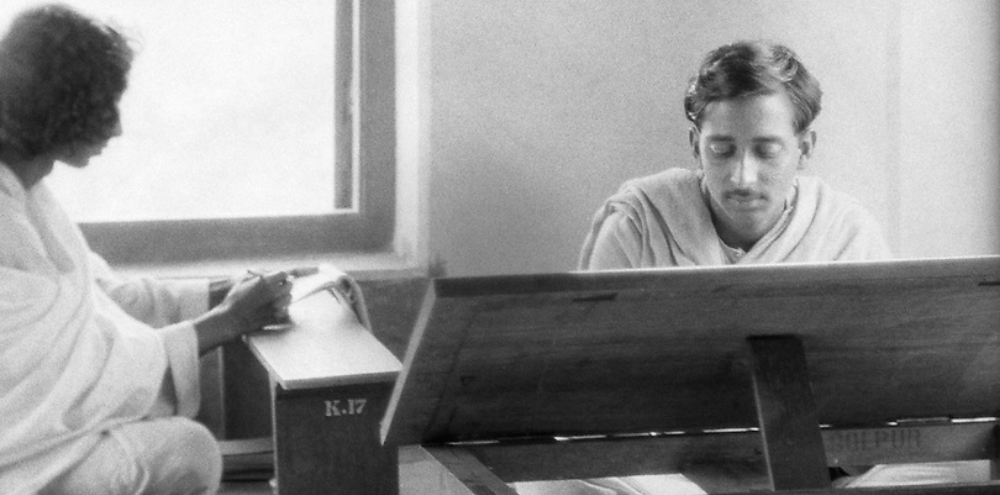

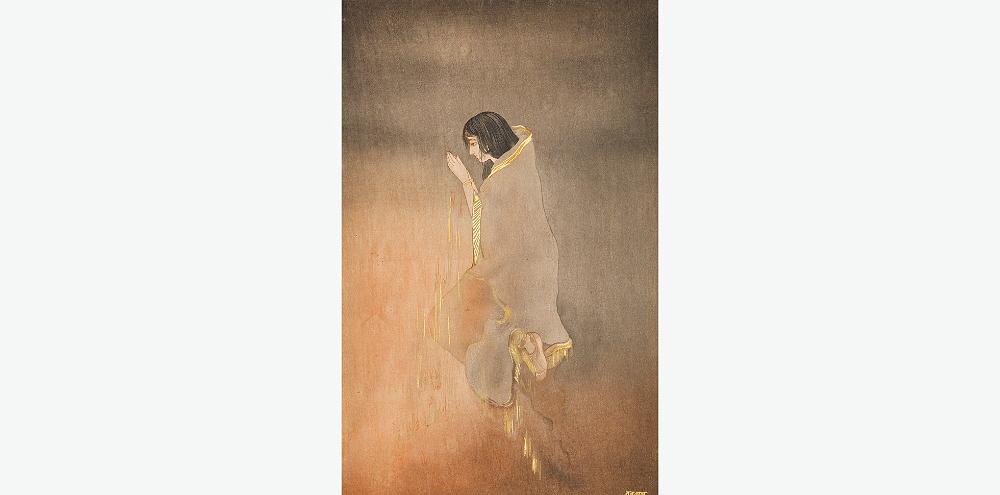

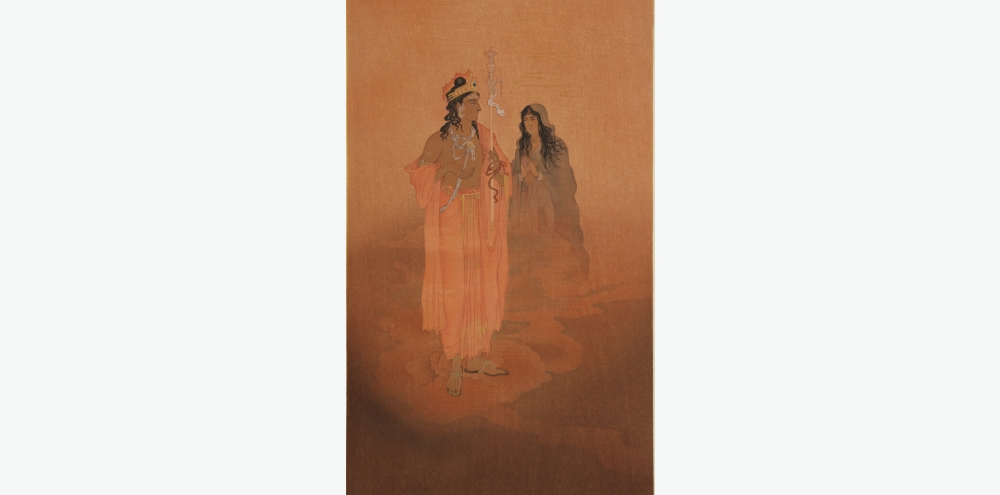

The bucolic site of Shantiniketan was first founded as an ashram by Rabindranath’s father, Debendranath, in 1862. In 1901, Rabindranath transformed the site into a school, with five teachers leading five students, including his own son. Tagore saw the school as an ideal extension of the tradition of the ashram in the forest, from which ancient Hindu texts such as the Upanishads had evolved. With trees enveloping the site, an open-air education was central to the school’s approach, encouraging students to feel free in spite of a formal learning environment. Engagement with daily life also freed the school and students from the lineage of the Bengal School movement, as students and artists could look beyond mythology, religious figures and narratives for inspiration for their work. Tagore sought to soften the boundaries between art and craft, promoting applied arts alongside fine arts in creation of a new visual culture. Textiles, book illustrations, murals and decorations for festivals became important elements of this new language.

During these early years of growth, Tagore became the first non-European winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, which would bring attention to Shantiniketan and all of his endeavours. Despite the fact that the Nobel Prize and translations of Tagore’s poetry helped finance the school, funding remained inadequate, particularly as he refused to accept monies from the colonial government. In time, the art school Kala Bhavana at Shantiniketan would become a key site for progressive art education, with some of India’s most important 20th-century artists, including Nandalal Bose (1882–1966), KG Subramanyan (1924–2016) and Ramkinker Baij (1906–80) studying and teaching at the school.

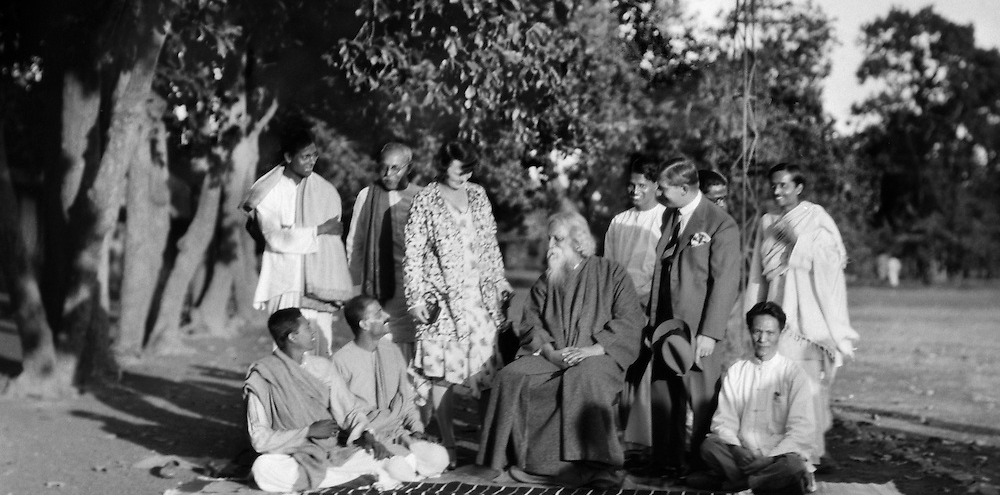

Confluences with Global Art Institutions and Individuals

Tagore was an internationalist across all of his work, whether in the language of his poetry or the administration of his school. A particularly impactful example of this is his meetings and interactions with Viennese art historian Stella Kramrisch (1896–1993). Tagore met Kramrisch in England in 1919, and invited her to teach at the Kala Bhavana. While she arrived with expertise in Western art, Kramrisch’s stay in India led to inimitable and historic contributions to the field of Indian art history over the next seventy years.

Furthermore, her arrival in India also brought the avant garde modernist Bauhaus movement to Calcutta in 1922 and fostered a new level of international and cross-cultural dialogue that followed Tagore’s ideals. For instance, the Bauhaus School’s first international presentation in Calcutta, showcased works by leading European modernists such as Paul Klee (1879–1940) – who would have a lasting influence on Indian modernist artists – alongside leading artists in India. There were structural, pedagogical and artistic parallels between the Bauhaus School founded in Weimar, Germany, some 300 km from Berlin, and Tagore’s Shantiniketan. Both schools promoted an approach to art-making that was conscious of its everyday surroundings and embedded in an awareness of history.

Kramrisch was instrumental at a practical level in bringing the Bauhaus works to India through her connection to artist and theorist Johannes Itten (1888–1967); on a symbolic level, her enduring presence in India engendered an international, even global dialogue between Indian and Western art and artists.

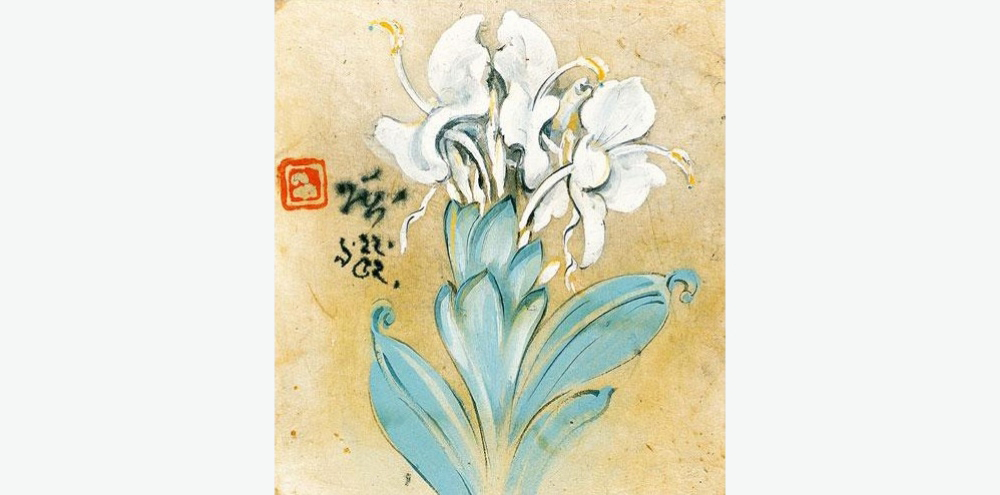

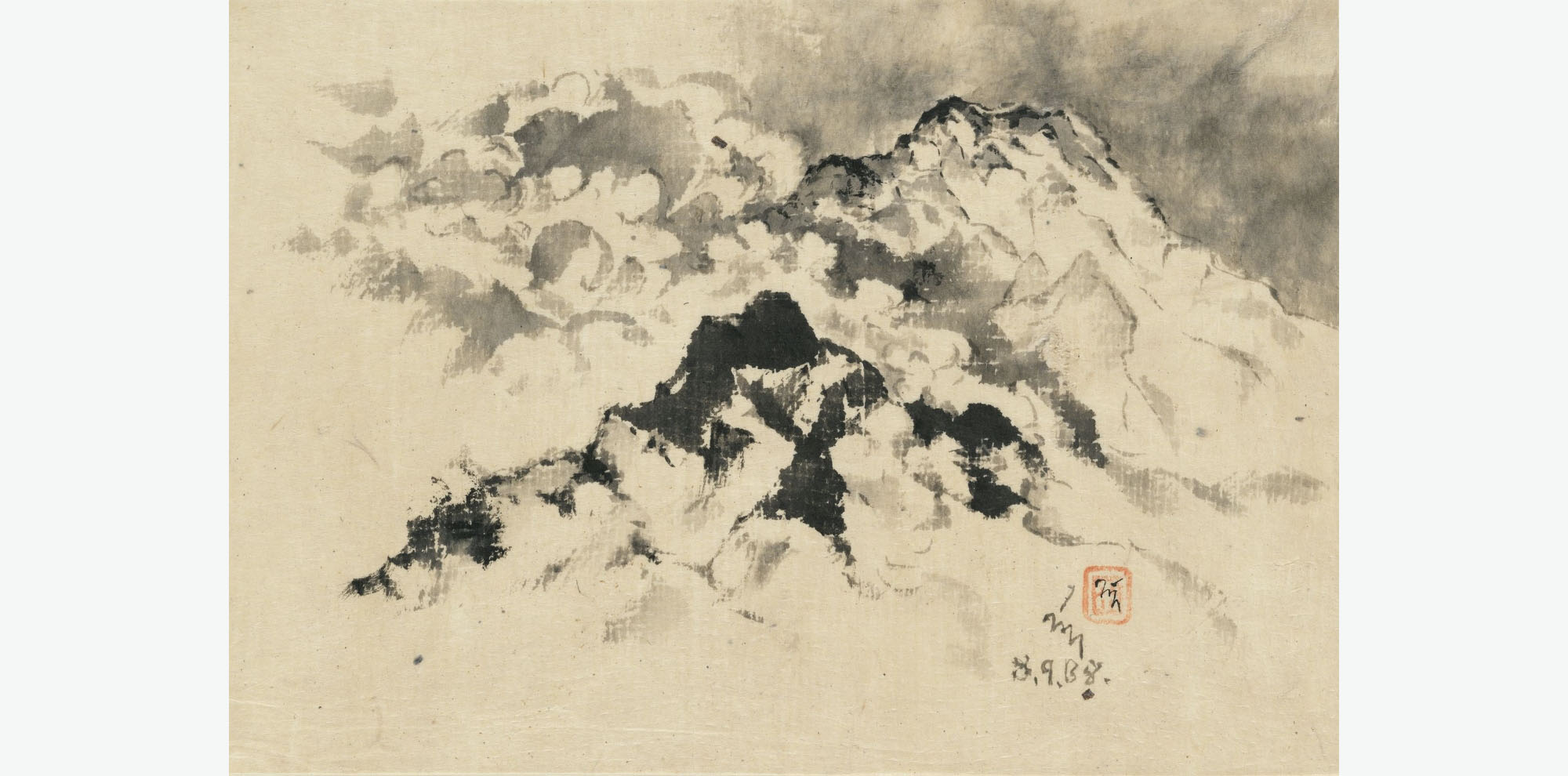

In addition to interactions with Europe, this period was also characterised by the rise of Pan-Asianism, which as we learnt in the previous Topic, was an ideology that promoted solidarity among nations across Asia. Through Tagore’s efforts, Shantiniketan became the centre for the catalysing of Pan-Asian ideals. In 1921, the school in Shantiniketan was transformed into Visva-Bharati, a university with an internationalist vision that adopted the motto ‘Where the world makes a home in a single nest’. These Pan-Asian values also seeped into the artworks of the time. For example, Nandalal Bose was trained in the art of ink painting during a trip to China in 1924, and began to incorporate elements such as Chinese stamps and techniques such as ink wash in his work.

In 1951, the Visva-Bharati University, under which Kala Bhavana operated, was absorbed into India’s formal university system. This resulted in the institution’s alternative pedagogical approach needing to adapt to the fixed syllabi of mainstream universities. Despite this, Tagore’s pioneering, prescient and unique vision of learning among nature continues to be influential in India and globally until today. The academic model at Shantiniketan and the extraordinary artistic and cultural exchanges that he fostered precipitated several key moments and movements in Indian art. These developed as independence from colonial rule approached in the mid-1940s and continued beyond.

In this Topic, we explore Rabindranath Tagore’s vision, and the pioneering institution that he established in Calcutta (now Kolkata). In case you’re curious to learn more about the artists and institutions mentioned here, refer to some of our articles below!

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Kala Bhavana Shantiniketan

- Bengal School

- Nandalal Bose

- KG Subramanyan

- Ramkinkar Baiji

- Stella Kramrisch

- Bauhaus

Further Readings