Towards Precision and Purity: Nasreen Mohamedi

In a 1969 journal entry, the artist Nasreen Mohamedi jotted the following:

Study the EYE

SPACE

Observe some objects in different light!

A cosmic rhythm with each stroke

South + Vibrations (Study)

Movement + Emptiness

Her words can be read as instructions that she leaves for herself, and speak directly to the elements of vibrations, sounds and emptiness that she attempted to attune herself to through her artistic practice. Without directly representing the world in images, her art was inspired by man-made environments, especially architecture and geometry as well as the underlying structures in nature. Her resulting works overlap ideas of the optical, metaphysical and mystical, mainly through gestures of pencil and ink on paper, experiments with organic forms, delicate grids and dynamic, hard-edged lines.

Mohamedi was born in Karachi (present-day Pakistan) in 1937. Her family moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1944 and lived between Bombay and Bahrain, where her father owned a photographic equipment business. She was made aware of difficult notions of mortality from a young age, losing her mother at the age of five and watching two of her brothers battle Huntington’s disease, which would claim her own life at the age of 53. Yet, she is known to have lived her life with unfailing courage and grace, her quiet but resolute demeanour reflecting the purity of form she sought to achieve through her works.

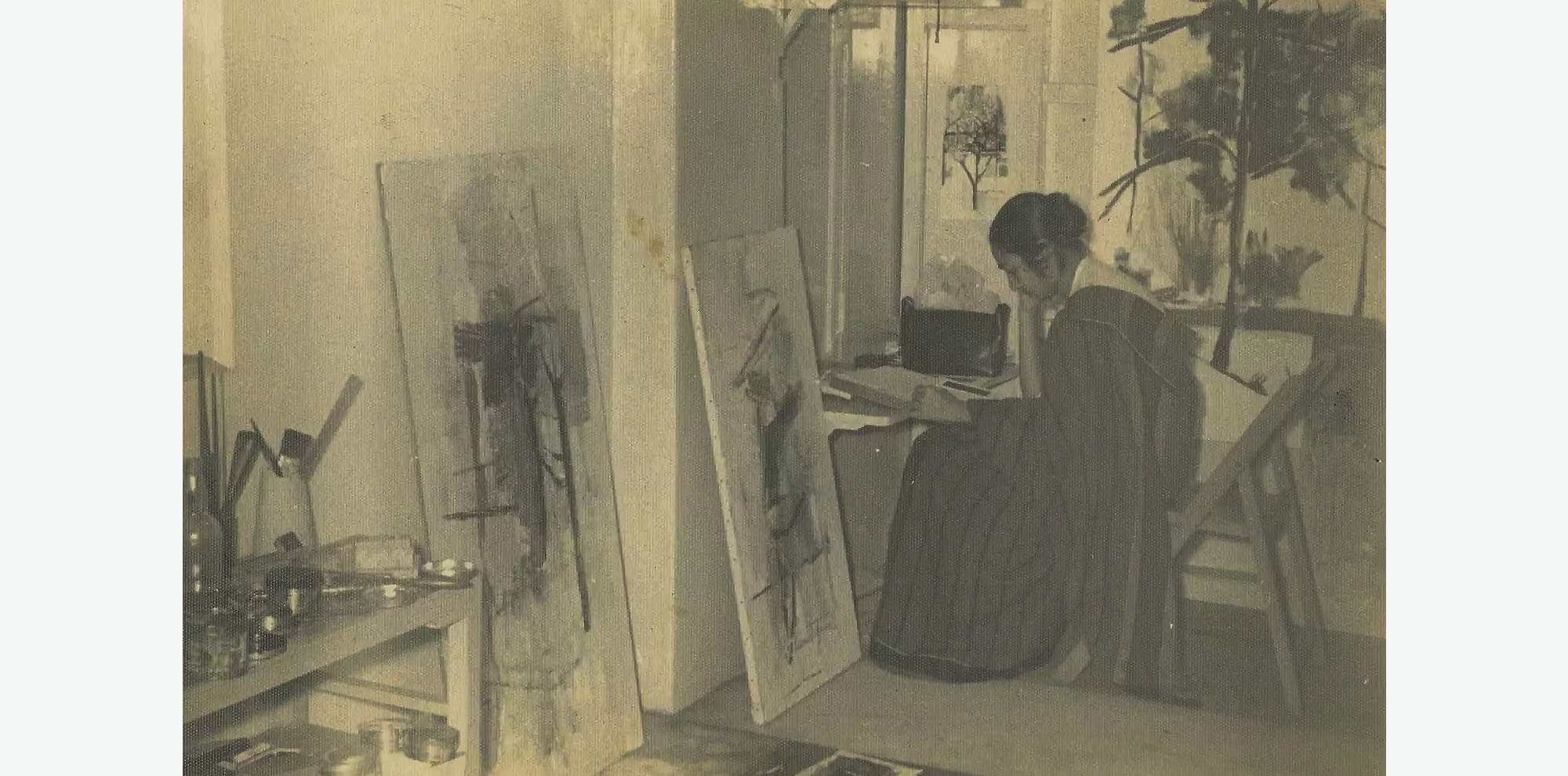

From 1954 to 1957, Mohamedi attended Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, which gave her early exposure to museum collections and the works of European abstract artists like Paul Klee (1879–1940) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944). She returned to Bombay in 1958 and worked out of the Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute, an experimental artists’ space that was frequented by seminal artists such as MF Husain (1915–2011), Akbar Padamsee (1928–2020), Nalini Malani (b. 1946) and Tyeb Mehta (1925–2009). It was also here that she met and was mentored by Vasudeo S Gaitonde (1924–2001), whose work we saw in the previous topic. Both shared an interest in Zen Buddhism and mysticism, and an influence of his abstract sensibilities is evident in her works following this period.

Although her works are predominantly undated and untitled, it is possible to follow the trajectory of her practice in phases.

Beginnings: Turning to Abstraction

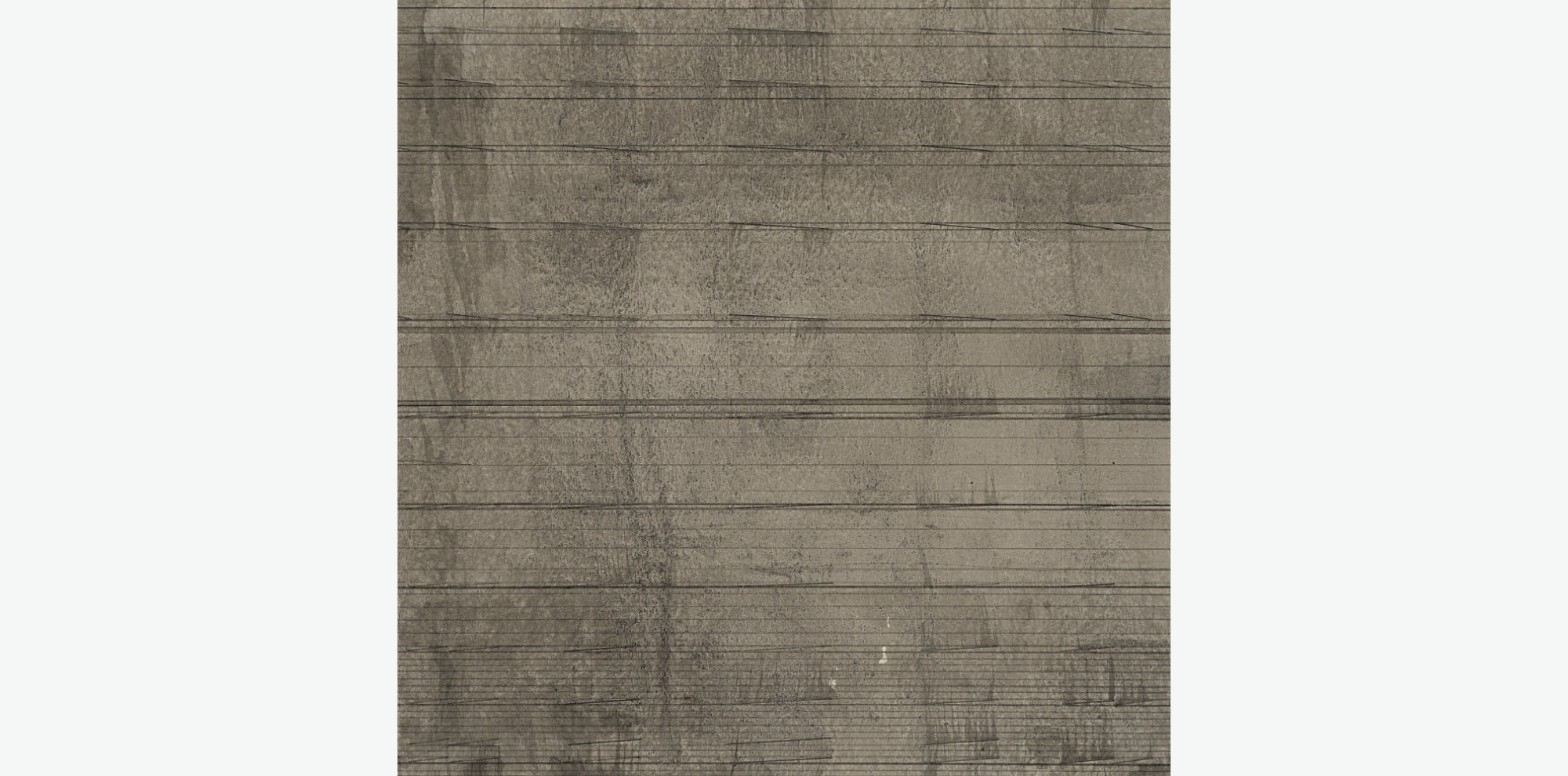

The 1960s were important in Mohamedi’s personal life and artistic practice. Upon receiving her diploma in fine arts, she travelled across the world, from Turkey, Iran, Karachi and London to Bahrain. This was also a period of greater interest in philosophical systems, poetry and ghazals as she grappled with questions of faith and spirituality. Her works from this period are imbued with a kind of lyrical but frenzied abstraction. Using ink wash and a dry brush technique, her mark-making could be read as withering forms of nature such as isolated branches and dried leaves. Her colours begin to fade and are substituted for monochromatic compositions that are typical of her practice from this point on.

Experiments with the Grid

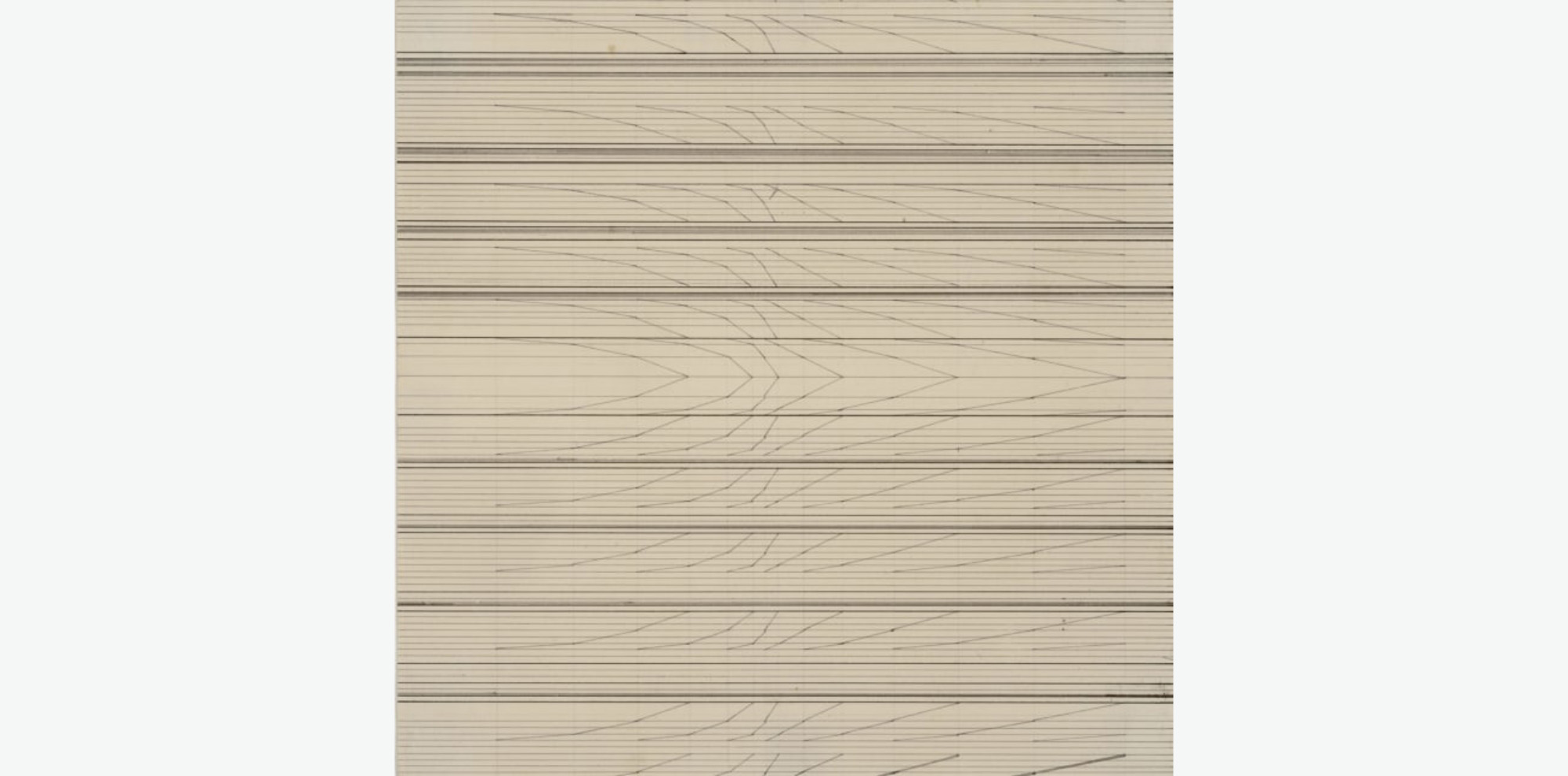

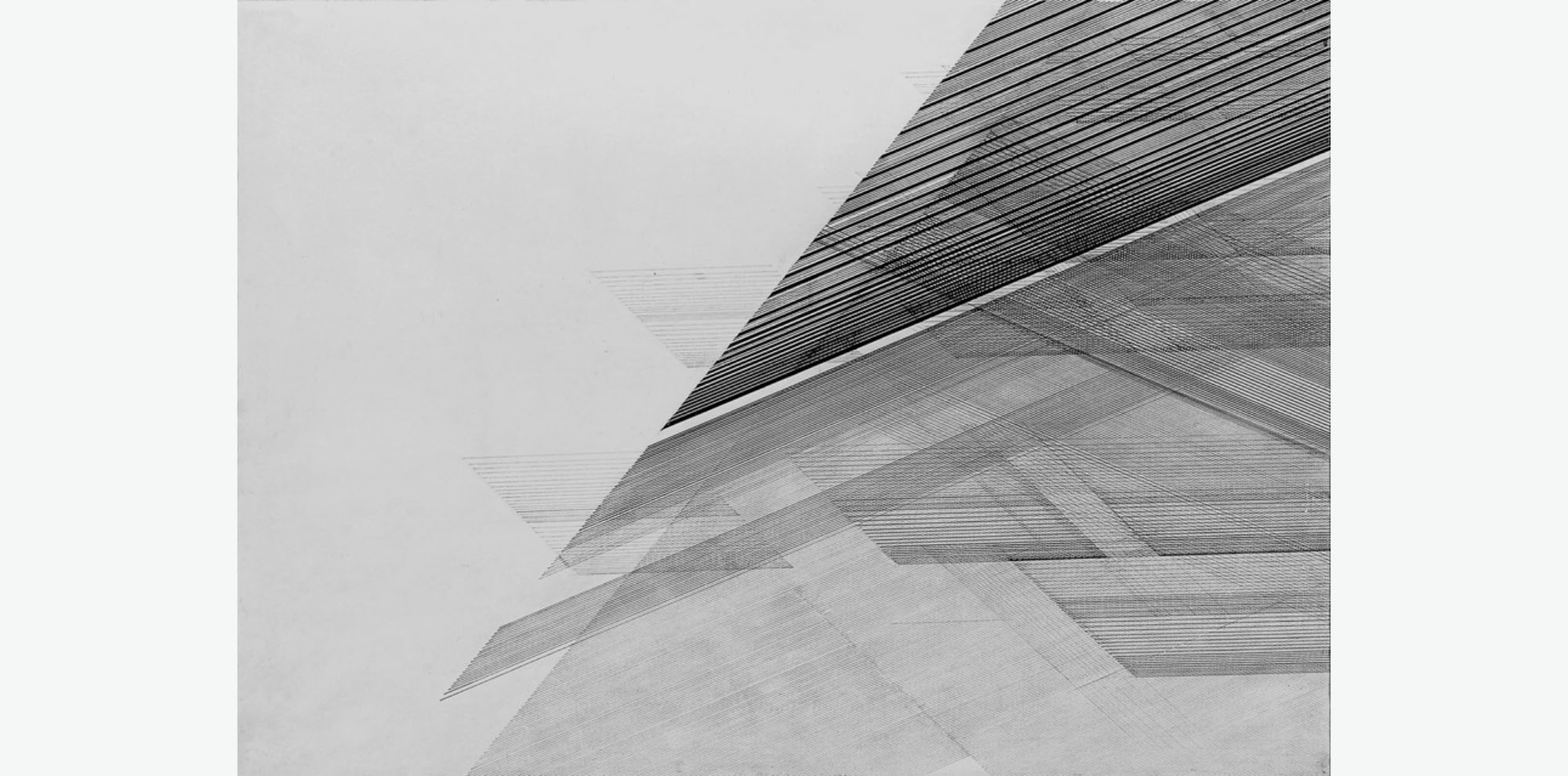

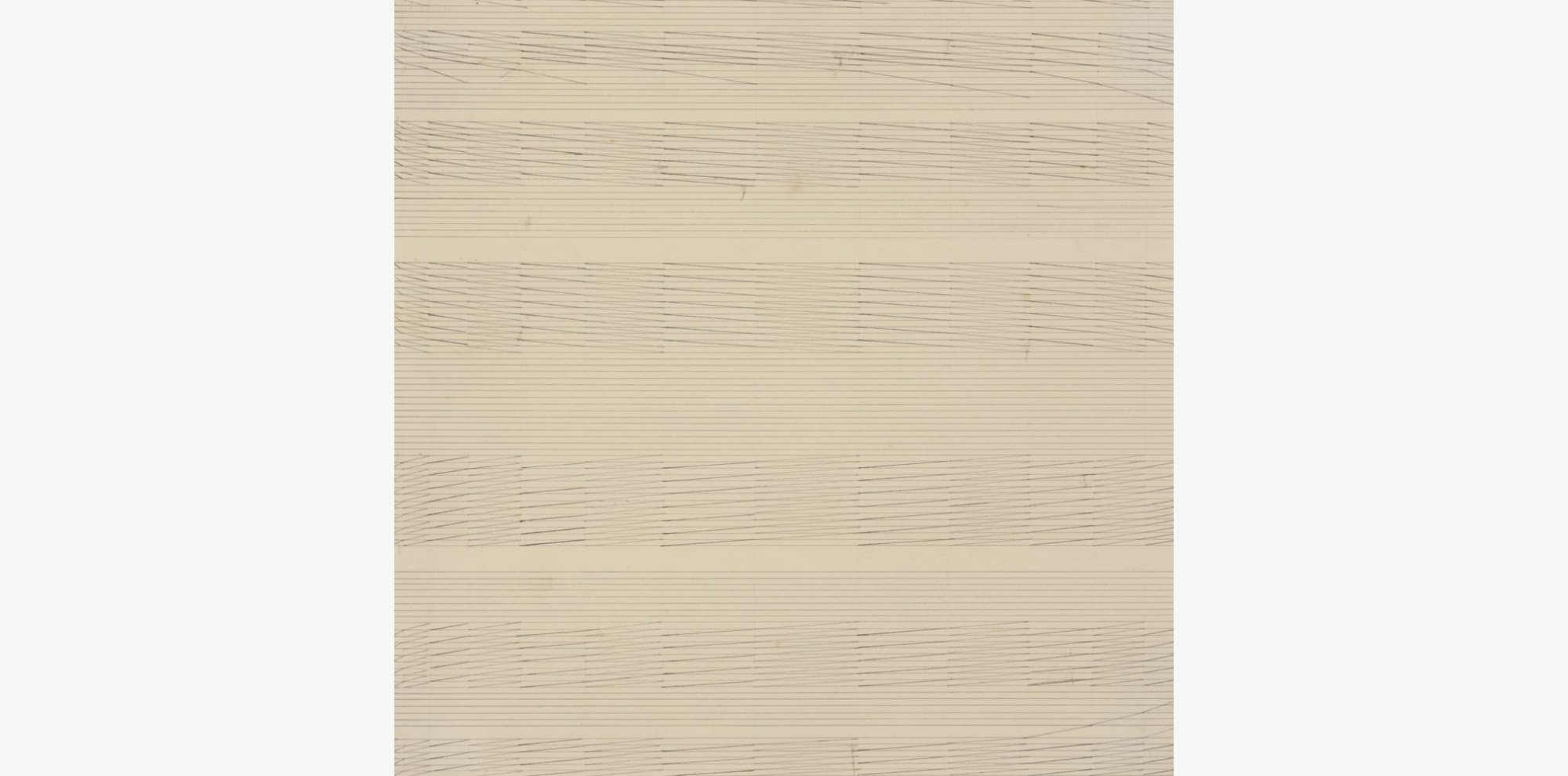

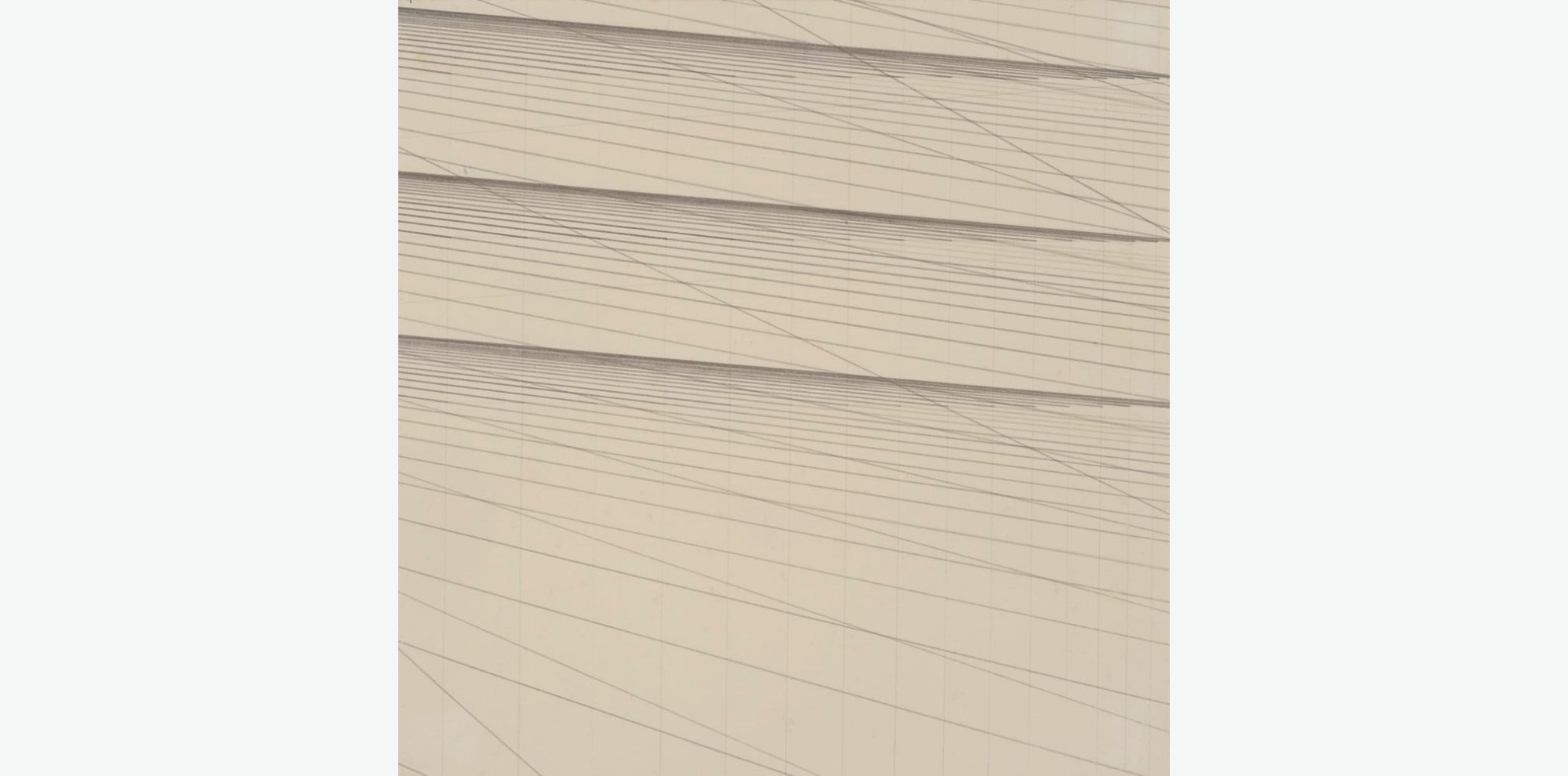

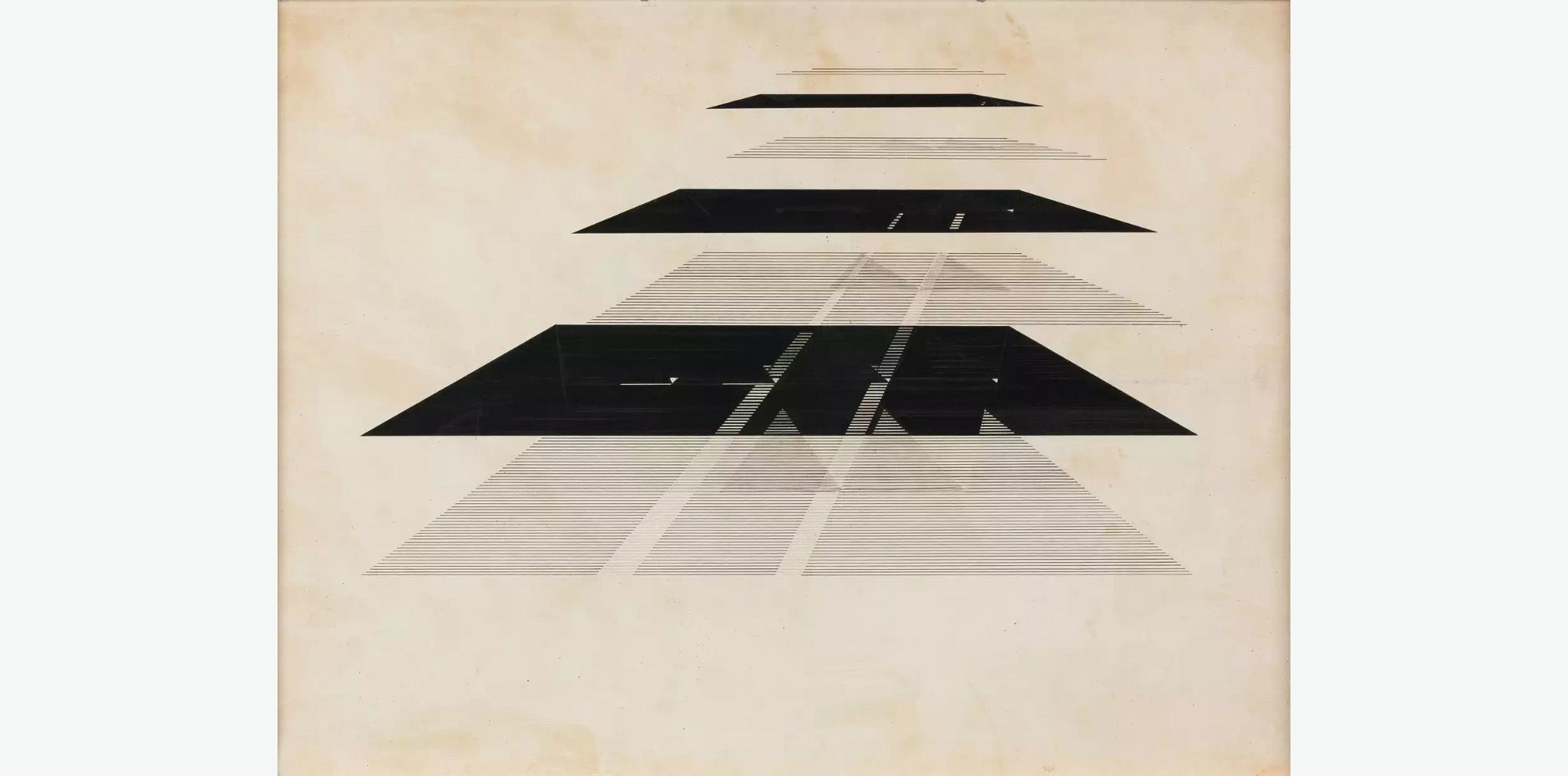

Over time, Mohamedi began to look towards rectilinear forms and then, the geometric grid as a template for her work. For instance, her pared-down canvas (Image 9) from 1965 features vertical and horizontal axes to structure the forms in the composition. Through her adoption of the grid, Mohamedi was following a long tradition of twentieth-century international artists who had also used this to structure their works and ideas. Some artists used the grid as a mechanical or geometric form, one that could be easily replicated, and could structure the picture plane. Contrastingly, Mohamedi’s drawings (Images 10, 11) intentionally break away from the rigidity of that form, by incorporating lines that veer away from the strict horizontal and vertical axes, and show fine traces of her hand moving over the paper.

A compelling example to consider is her Untitled work from around 1975 (Image 10), which is structured around the interval or spacing of the vertical line, with somewhat wider bands in the centre of the paper as compared to the edges. Within many of the squares or rectangles created by the intersection of horizontal and vertical, Mohamedi has also inserted a gently sloped diagonal line. The diagonals occasionally veer beyond an individual segment of the work, creating a cadence through the disruption of geometry. Throughout these works, Mohamedi’s forms are precise, but also retain the intimacy of the artist’s hand in a way that many artists working with the rigidity and precision of the grid tried to avoid.

Abandoning the Grid

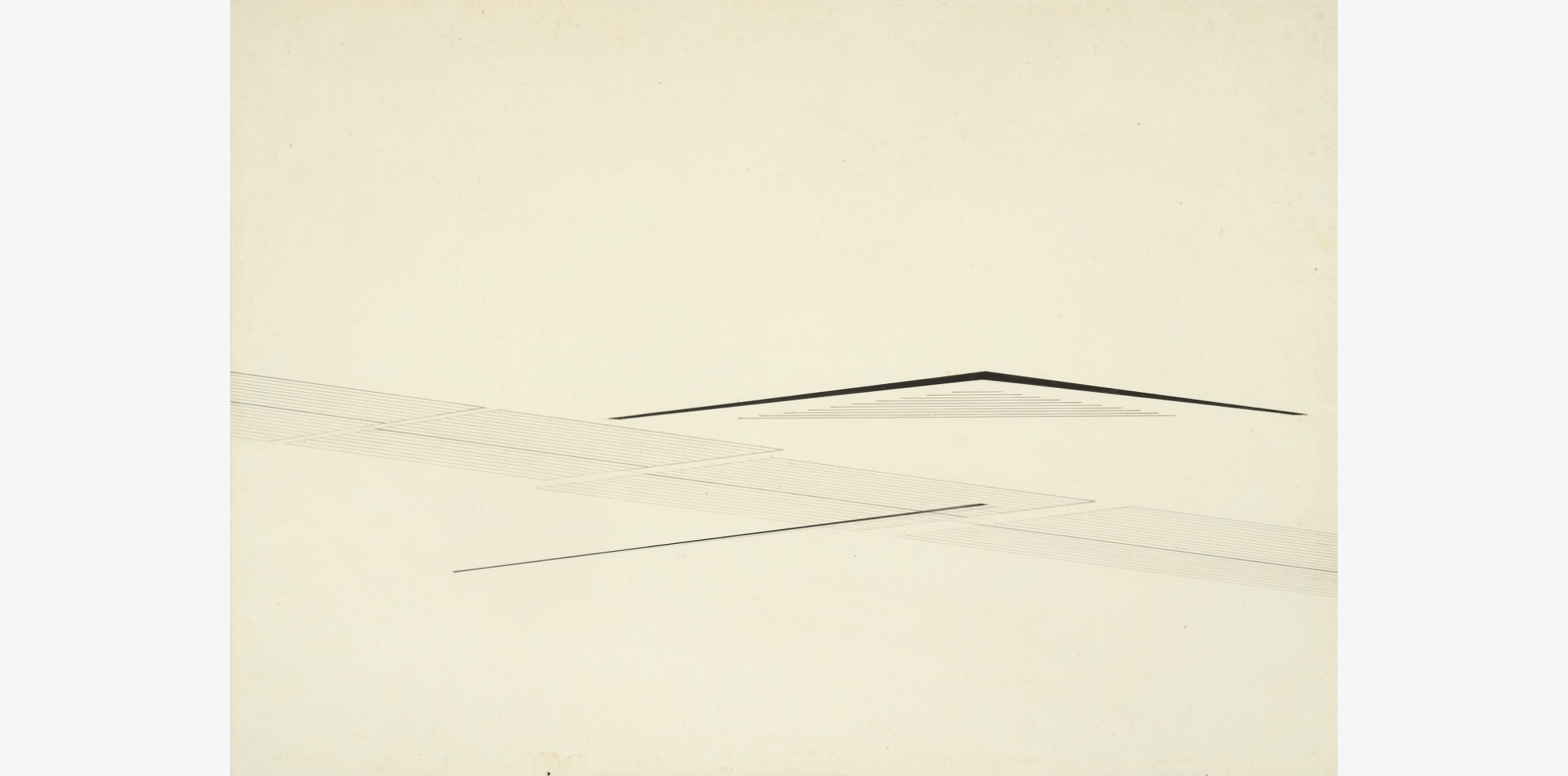

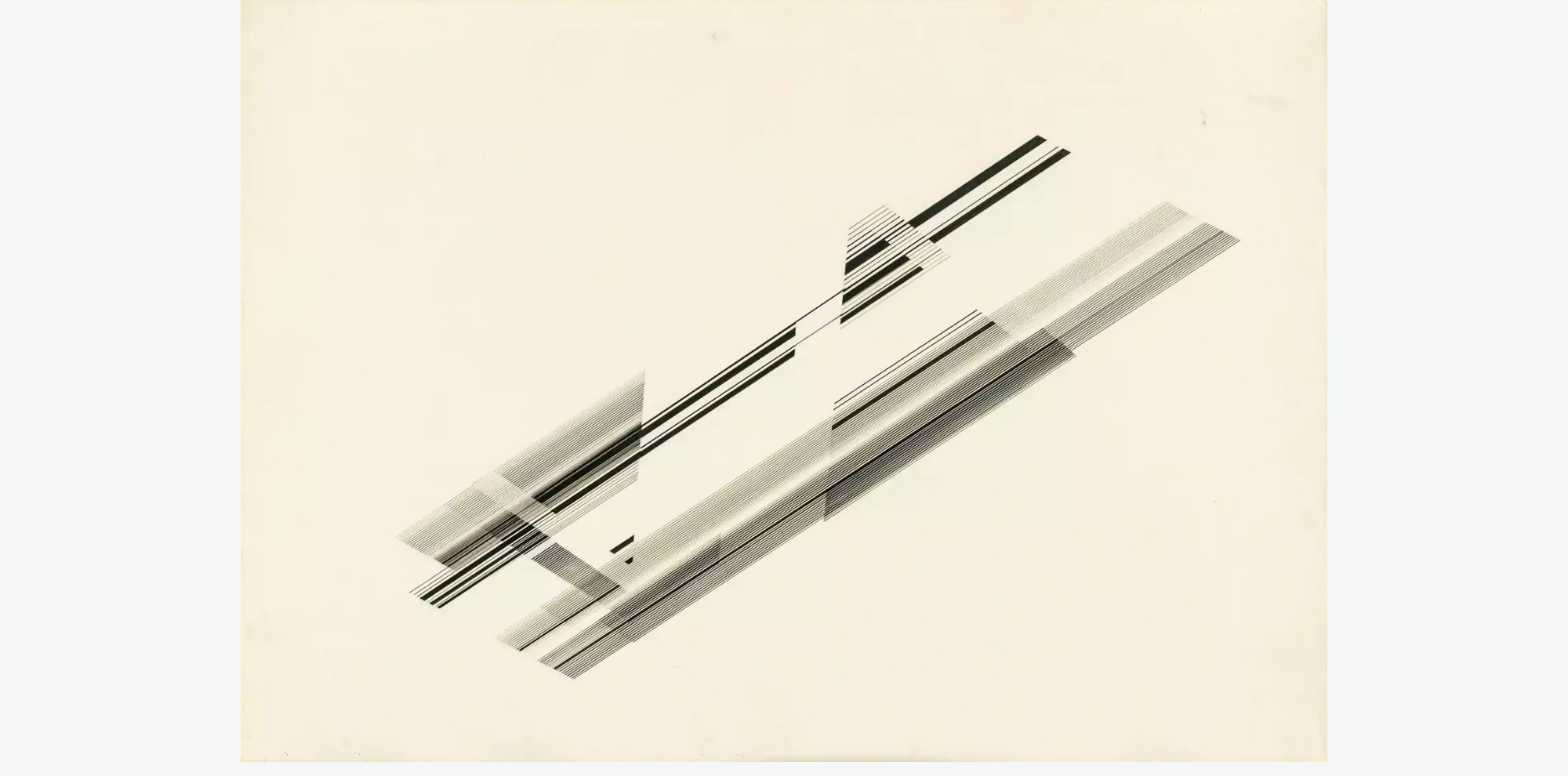

Mohamedi’s grid-based works were characterised by the use of the entire pictorial space, with parallel lines of different thicknesses sprawling across her compositions. By the 1980s however, she began to abandon the grid as a compositional device, allowing more space to breathe into her compositions with geometric forms like arcs and diagonals that freely floated in the centre.

In an Untitled work from that decade (Image 13), a series of light to medium-weight diagonal lines running from left to right are concentrated in the middle of the page, while a smaller group of lightly drawn lines hover above. The lines at the centre are all bisected by three black corners of different sizes and weights. All of these lines and forms float on the page, never extending to the edge.

Later Works

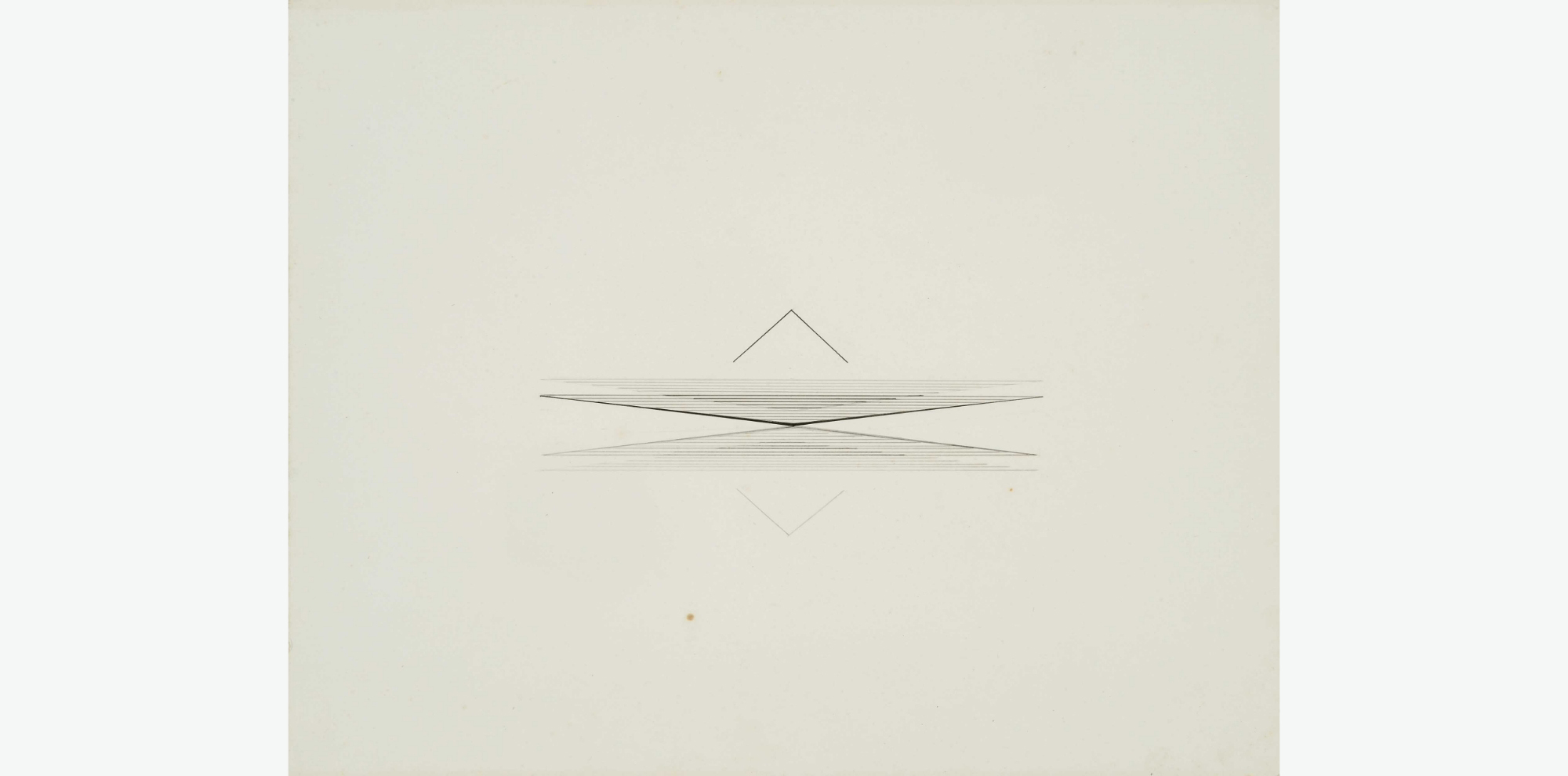

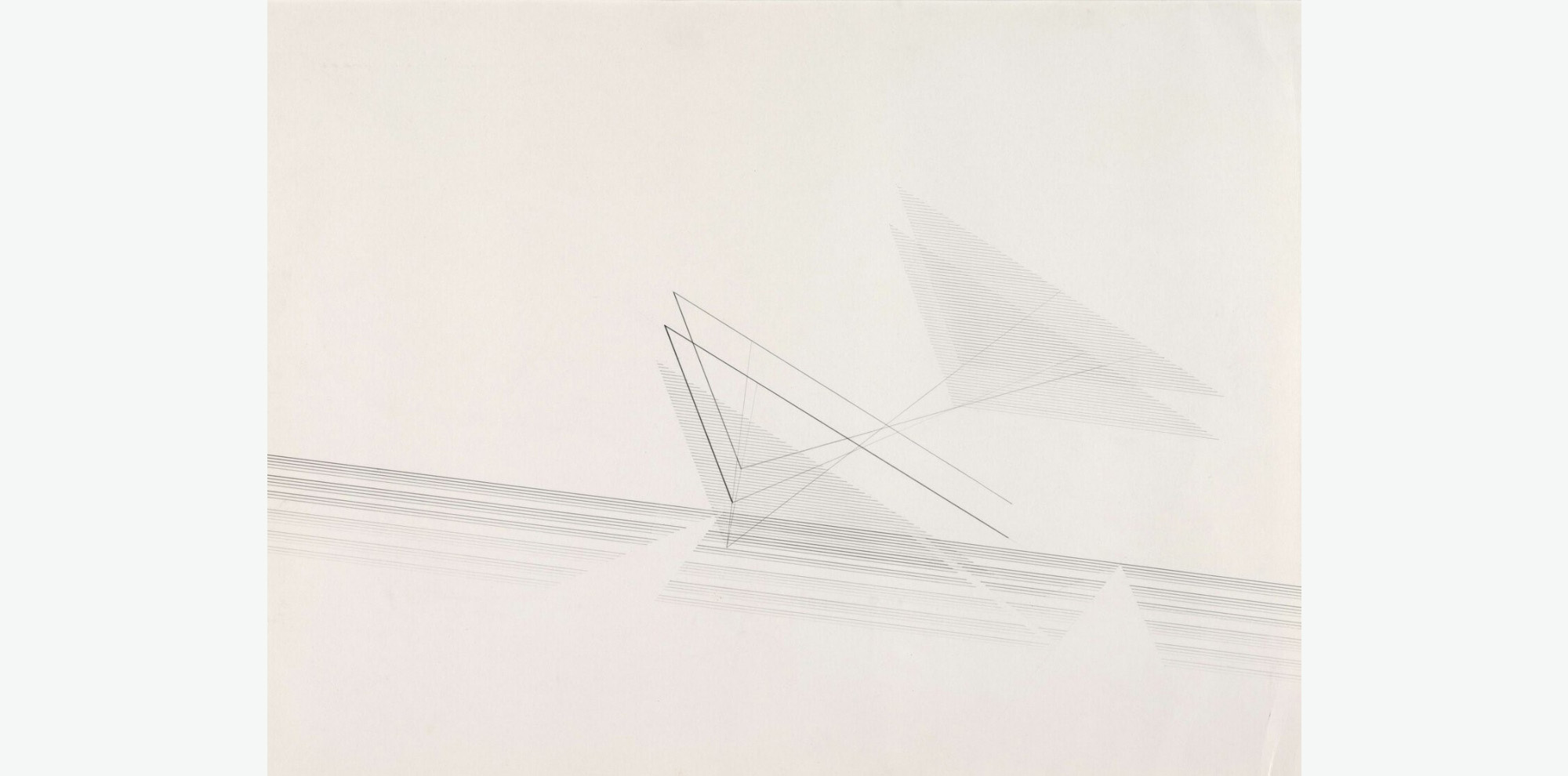

By the last phase in her artistic journey in the late 1980s, Mohamedi’s health had deteriorated with the progression of a neuro-muscular disease that prevented the use of the precision tools that allowed for her exacting geometric compositions. Her works were now imbued with a sense of calm and interiority, with large areas of empty space, the light pressure of the pencil and lines that are barely perceptible. It is almost as if Mohamedi was freeing herself from her compositional plane, leaving behind almost no authorial trace.

Within the trajectory of Indian modernism, Mohamedi’s forms stand apart in their quiet elegance and simplicity. Between 1972 and her death in 1993, Mohamedi lived in Baroda (present-day Vadodara), where she taught drawing at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Maharaja Sayajirao University, whose history we will explore in the next lesson. While her contemporaries in Baroda, such as Gulammohammed Sheikh (b. 1937) and Vivan Sundaram (1943–2023), were leading a movement around narrative figuration and constructing increasingly packed compositions on canvases, Mohamedi continued to pare down her visual elements. Shifting focus from complex imagery and social and political narratives, her practice urges us to pay attention to the formal qualities of a work of art.

Even as the art critic, Geeta Kapur (b. 1943) situates Mohamedi ‘within a great lineage of metaphysical abstraction’, she notes that ‘there will never be anyone like Nasreen again in the Indian art world. There will be geniuses and transgressive rebels, but none so noble’.

Check out the following links to discover Nasreen Mohemadi’s artistic explorations, and some of the artists she associated with.

- Nasreen Mohemadi

- VS Gaitonde

- Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda

- Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute

Further Readings