Ancient India, Figuration, and History in Contemporary Indian Art

Across Indian modern and contemporary art, we often find references to figurative imagery that dates back to the subcontinent’s ancient past. Surviving artworks from the region that date back centuries have served as pedagogical tools as well as sources of inspiration for artists. Let’s examine how representations of the Buddha, Pratihara Sculptures, Chola Bronzes and other ancient temple sculptures have variously informed the practices of Indian artists upto the present moment.

Early depictions spanning representations of the Buddha, Chola Bronzes and ancient temple sculptures .

Documenting and learning from the past

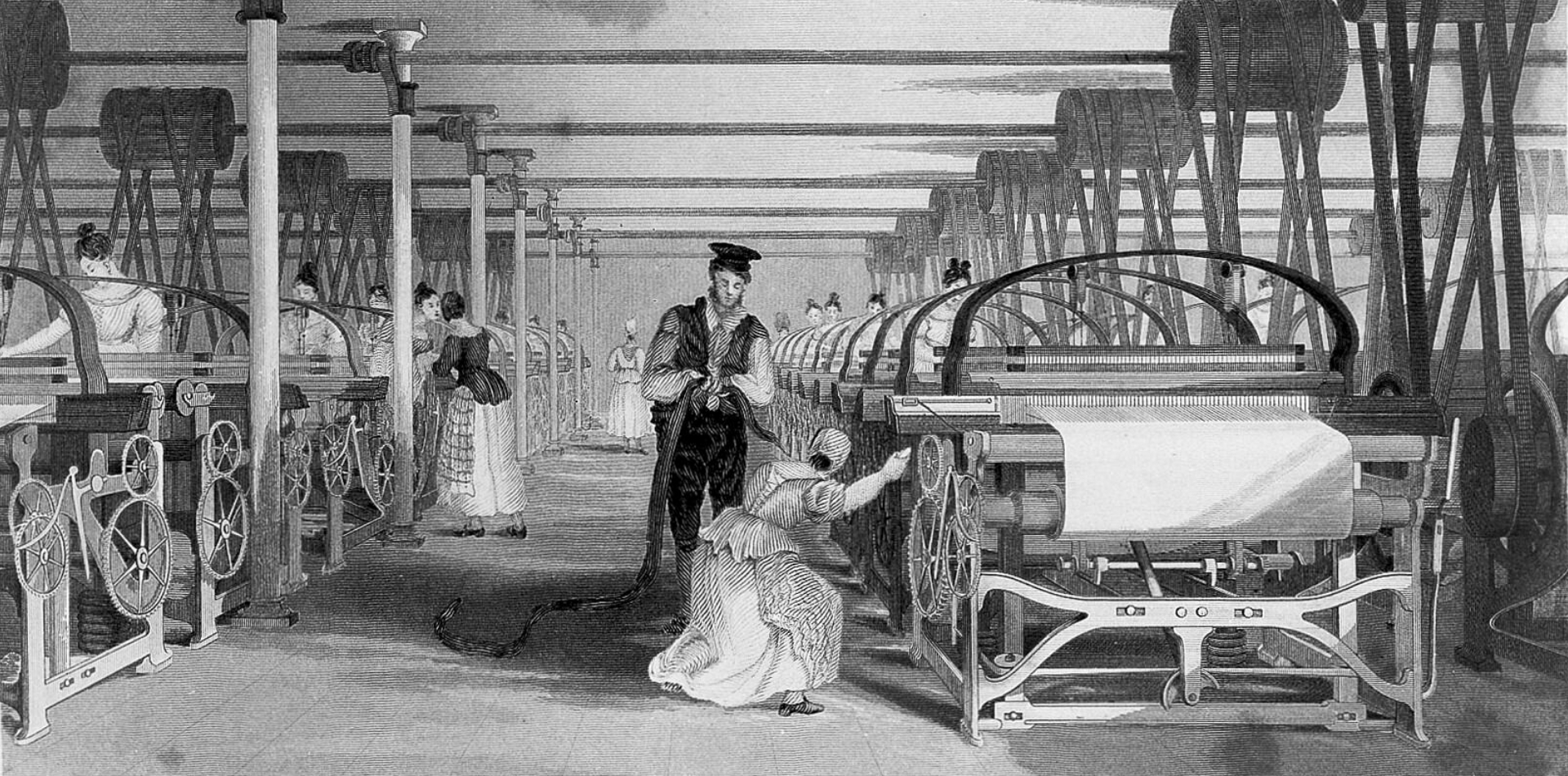

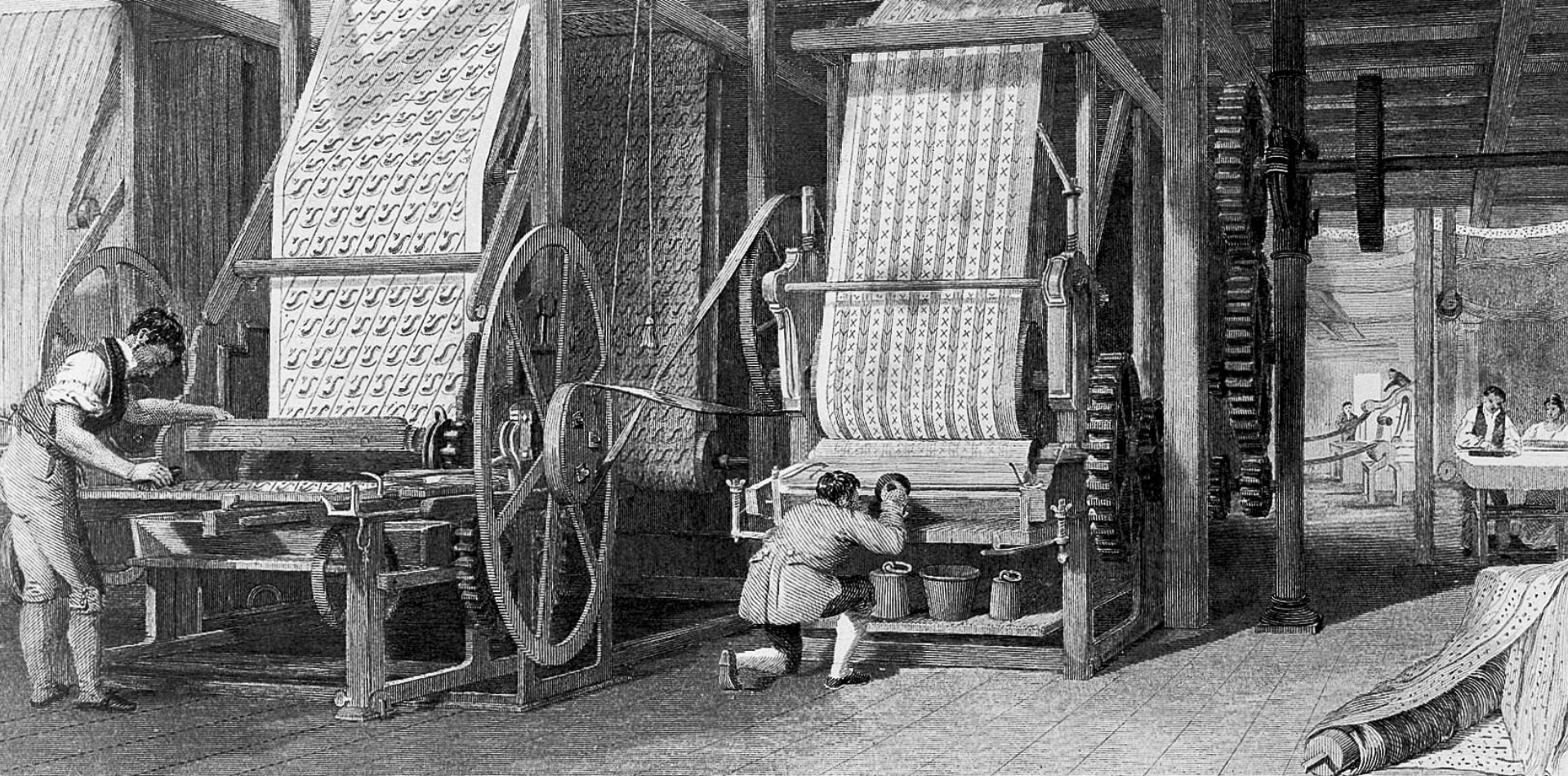

Conversations around the place of Indian art in relation to its European counterpart arose during the period of British colonial rule in the 18th and 19th centuries. As part of the East India Company’s project of inculcating taste and skill in Indian art, they established art schools and institutions to promote formal training and the appreciation of art in India. Ancient Indian monuments appeared at the forefront of this practice and were studied by art students to hone their skills, and gain an understanding of the subcontinent’s histories.

The renowned Ajanta Cave paintings near Aurangabad, which relay narrative tales of the previous lives of the Buddha, became symbolic of something that was “quintessentially Indian.” In the 19th century, amidst their “re-discovery” by the British officer John Smith, the imagery on the caves led to several forms of documentation across different schools of art that sought to emulate and preserve the country’s heritage.

The British artist John Griffiths, of the Bombay School of Art, for example, worked with seven of his students to create notable copies of some of Ajanta’s paintings in the 1870s and 1880s. His attempts at documenting the caves, however, have been critiqued by certain scholars for being too “Europeanised.” This is evident in their use of techniques such as realism, the use of light and shadow, and overemphasised perspective – elements that were not found in the original paintings.

These expeditions continued throughout the first half of the 20th century and evolved over time. Artists Abanindranath Tagore and then Nandalal Bose took groups of students from the Calcutta School of Art and Visva-Bharati at Santiniketan to Ajanta. Their students attempted to capture the true spirit of the original work from the caves, retaining their imagination and fervor, such as the stylised and unnatural anatomies of the figures. Such paintings eventually informed an emerging idea of an indigenous style of work, leading to a digression from Western academic art that was taught in 19th century Bengal.

Such references and representations show us the direct link between ancient India and the development of art in the 20th century.

Tracing Lineages

Let’s now turn our attention to how contemporary Indian artists have also sought to situate themselves within the long lineages of art from the subcontinent.

Contemporary artist Sudhir Patwardhan’s painting, The Eclectic (2005)features the artist standing in his studio, looking out of a window facing a surreal landscape. Among the various pieces of furniture and canvases that line the walls of his studio, we find a sculptural head discreetly propped on top of a cabinet in a corner. A closer look reveals that this is a representation of Shiva that seems to be based on the front face of a three-headed Pratihara sculpture from the 10th century. On the other side of the room we see a painted canvas of a Chola bronze sculpture angled against a bookshelf on the floor. Chola bronzes are undoubtedly some of the most striking examples of ancient art from India, commissioned by temples and dressed and adorned for ritual use.

Patwardhan’s engagement with the past goes beyond the emulation that the 19th and 20th century artists practiced. By including a self-portrait within the composition he traces a direct trajectory from the 10th century, to the present day.

Recontextualizing Histories: Subverting traditional meaning

LN Tallur, known for his large-scale sculptures and installations, often also engages with art historical imagery in a unique way. The artist recontextualises references from historical Indian sculpture through imagery that critiques contemporary culture and society.

His works Obituary Note (2013) and Unicode (2011) both reference traditional iconography of the Hindu god Shiva Nataraja encircled by a flamed halo as we see here. However, in Obituary note, Tallur replaces the central figure of the deity with charred wood taken from funeral pyres in India.The wooden core of the work invokes notions of world destruction, while cleverly nodding to the cremation ground upon which Shiva Nataraja dances. Similarly, in Unicode, the artist replaces the central deity with a concrete ball embedded with coins, critiquing the negative effects of capitalism and urban development on history and tradition.

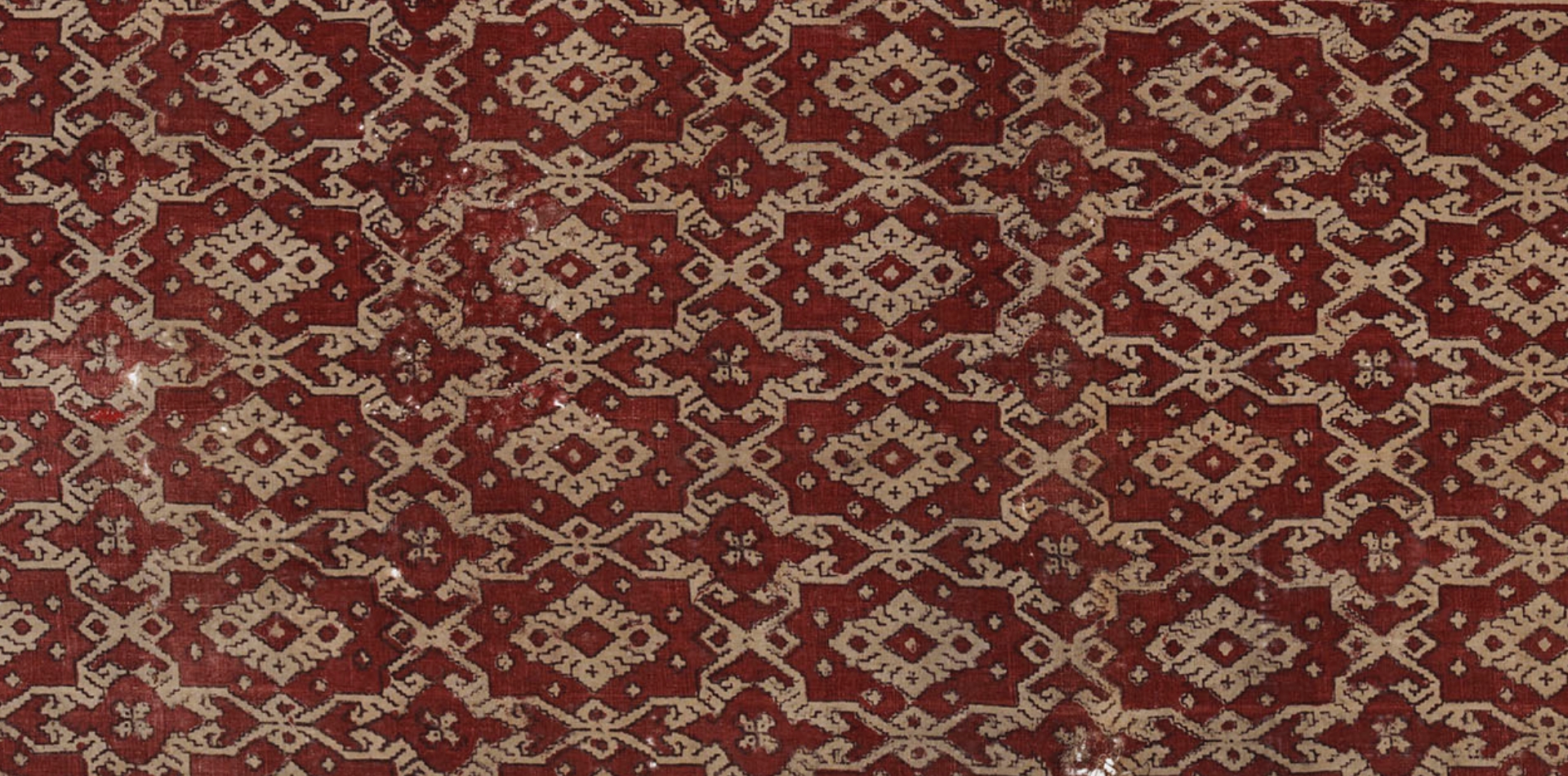

In another work titled Milled History (2014), Tallur approaches the critique of decay and destruction of tradition more literally. Here, a wooden copy of a temple sculpture, resembling Vishnu figures from Tamil Nadu, was kept in his backyard and allowed to be infested with termites and ants. He then digitally scanned the termite-ravaged figure and milled a replica of it in sandstone, thereby creating a sculpture that represented the slow wreckage of history.

Conclusion

The diverse ways in which artists have engaged with art history, reveal the importance that the past continues to hold for our present and future. As we go through the other topics in this lesson, we’ll explore how traditional forms of ancient Indian art lend themselves to constant experimentation and redefinition, allowing us to look at art history in more imaginative ways.