Creating Community: Cholamandal

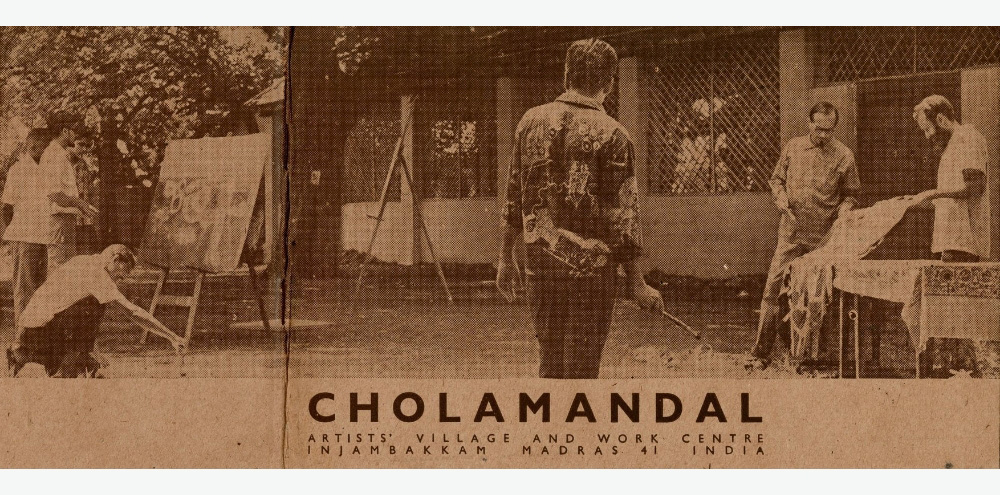

A few kilometres away from the city of Chennai in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu, in an unassuming location off the side of a highway lies an artists’ complex known for its unique conception. Founded in 1966 by the artist KCS Paniker (1911–1977), this site, the Cholamandal Artists’ Village, comprises a gallery, a workshop space, houses for resident artists and outdoor sculptures. Let’s explore the history of this community and its unique place in the history of Indian modern and contemporary art.

Setting up Cholamandal

Since the mid-19th century, centres for art education in south India have created curriculums combining European styles with regional artforms, beginning with the establishment of the Madras School of Arts and Crafts in 1850 by the British surgeon and artist Alexander Hunter (1816–1890). From 1957–1966, the School was helmed by KCS Paniker, who was crucial in introducing an awareness of Euro-American modern art while initiating a programme on nativism and indigenism that led to the emergence of the Madras Art Movement. This movement integrated ethnic folklore, rituals, folk arts, and crafts and art commissioned by historic dynasties in south India.

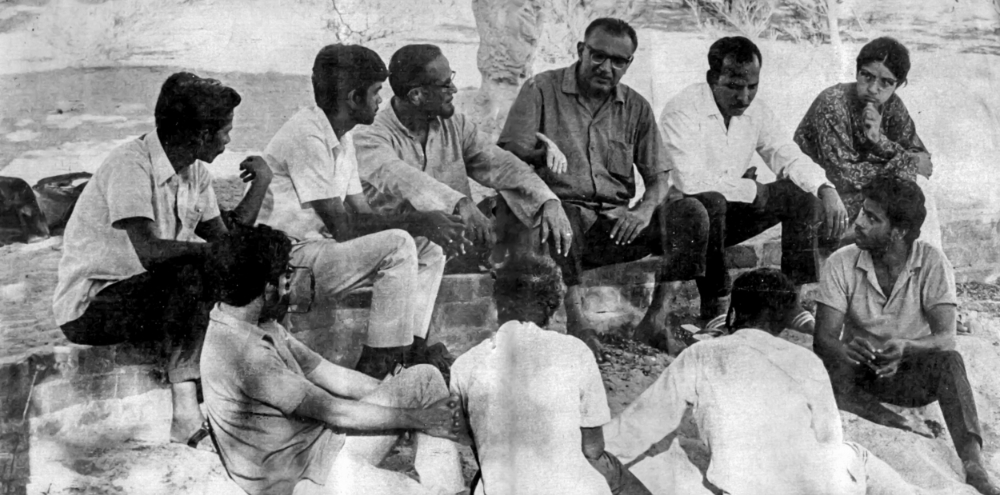

Watching his students struggle to find a market and audience for their works, Paniker sought to create a space of community where their creative expression could thrive and the commercial potential for the Indigenous art forms could be leveraged. With Paniker’s support, artists associated with the Madras School migrated to Cholamandal and set up a communal village setting. Every home here was built by an artist, with Paniker refusing government money for the project. The first artists who moved in 1966 were mostly fellow teachers and students in search of a new artistic idiom, one which supported tradition, but not simply the re-creation of the past.

Let’s take a look at the divergent practices of two artists associated with Cholamandal to understand the varied creative expressions fostered within this artistic community.

The Personal and the Fantastical: K Ramanujam

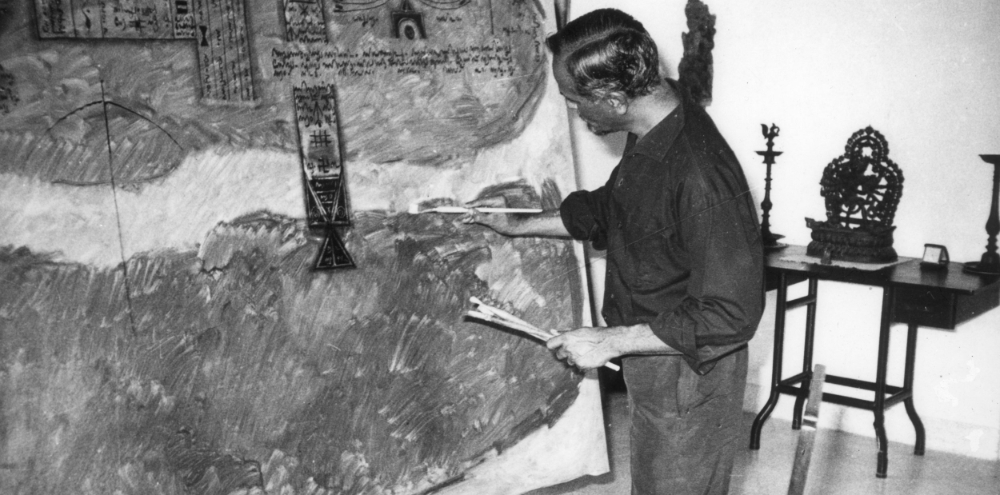

One of the most important artists associated with Cholamandal was K Ramanujam (1941–1973), who moved to the village in 1971 through Paniker’s influence. He developed a unique language of figuration that integrated Indian folktales with European Baroque painting and his own fantastical dreams. Stylistically, his practice is marked by careful use of the line amidst saturated colour fields. By the time he moved to Cholamandal, Ramanujam had started to gain recognition, and in 1972, the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa (1919–2003) commissioned him to create three murals at Hotel Connemara in Madras. Most of his works, however, were modest in size and deeply personal.

Let’s take a closer look at one of his paintings titled My Dream World. Here, two large mythical figures frame a small group of humans, who seem to be engaged in a communal and possibly ritualistic activity in front of a building dotted with rows of arches. While the iconography is legible, it is difficult to read a single narrative in the work. This is typical of the seemingly surrealist approach Ramanujam took, using his drawings as records of his dreams, as indicated by the title he has given to this body of work. A black and white ink line drawing from the same series, also titled My Dream World, shows related iconography with fantastical creatures amidst grand architectural framing. This painting shows the artist’s attention to minute detail even more clearly.

Despite developing a complex visual language that combined the personal, the sublime and the absurd, Ramanujam’s artistic practice remained on the margins even at Cholamandal and his work has sometimes been categorised as ‘Outsider Art’. Throughout his difficult life, he struggled with a speech impediment and alleged schizophrenia, and died at the age of thirty-three.

Another seminal modernist associated with Cholamandal was the painter, J Sultan Ali, known for his ruminations on Indigenous and folk traditions and iconographies.

A “More Indian” Art: J Sultan Ali

J Sultan Ali (1920–1990) left his home in Bombay in 1945 to study painting at the Government College of Fine Arts in Madras, later studying at the Madras Government Textile Institute. He was inspired by the Bastar community in central India and Indigenous art and also studied the work of British-born Indian anthropologist Verrier Elwin (1902–1964), who wrote about vernacular cultures and how symbols were used outside of classical art. He was determined to become ‘more Indian’, and introduced aspects of Hindu mythology and folk painting into his work. His paintings spanned figuration and abstraction, including brightly-coloured portraits of Indigenous women and grey or neutral evocations of Hindu deities, like Shiva’s ferocious avatar Bhairava. This work abstracts the deity, integrating elements of tantric art with ornamentation associated with figural forms of the god.

While J Sultan Ali’s biography and work are quite different from Ramanujam’s, looking at them together offers a perspective into the identity of Cholamandal, and how it could support a range of creative expression that integrated modern art idioms and Indian traditions.

As we’ve seen through the practices of the two artists, Cholamandal fostered a unique space for experimentation, resulting in practices that were diverse in both medium and form. Over the decades, Cholamandal has also become a major tourist attraction in Chennai. However, the site has shifted greatly in its organisation since its conception. It is now predominantly inhabited by homeowners who lease their homes to artists, and has been criticised for no longer accepting new artists, resulting in its number of resident artists dwindling to half in the present day.

Turning southwards from the Bengal, Baroda and Mumbai art schools, this Topic includes artists from Madras’ Cholamandal — some of whose practices have also been covered in the following articles:

Further readings