Shifting Art Worlds: Artistic Expressions in the Late-19th Century

Following on from the 18th century, when the East India Company established its rule across India, British officers began making efforts to inculcate European notions of taste and skill among the region’s audiences. This involved setting up art schools to promote formal training and art appreciation in colonial cities such as Calcutta (now Kolkata), Madras (now Chennai) and Bombay (now Mumbai). The traditional model of studying creative practices was based on a system of apprenticeship where students learnt from masters to whom they were fully devoted. The British academic system, which aimed to replace this, was led by economic motivations and offered practical knowledge necessary to produce artworks adhering to British tastes. This change, which coincided with shifting power structures across India, had a lasting impact on the systems governing the dissemination of art, the identity of artists, and the preferred styles and subjects portrayed. Let’s briefly look at some of these significant changes as well as how they ultimately resulted in artist-led explorations of an ‘Indian’ style of art.

Patronage

In India, art was historically commissioned by royal families, courts and aristocrats. When the East India Company gained administrative control over most kingdoms, the demand from local rulers started to decline. By the 1870s, British officers began to explore and collect Indian art, and art societies and exhibitions modeled on the British Royal Academy (Images 4, 5) gave artists the opportunity to showcase and sell their works to a broader public in Indian cities. This new generation of collectors predominantly favoured a style of naturalism — that involves representing things as we see them — in relation to drawings, paintings or sculpture.

Artistic Mediums

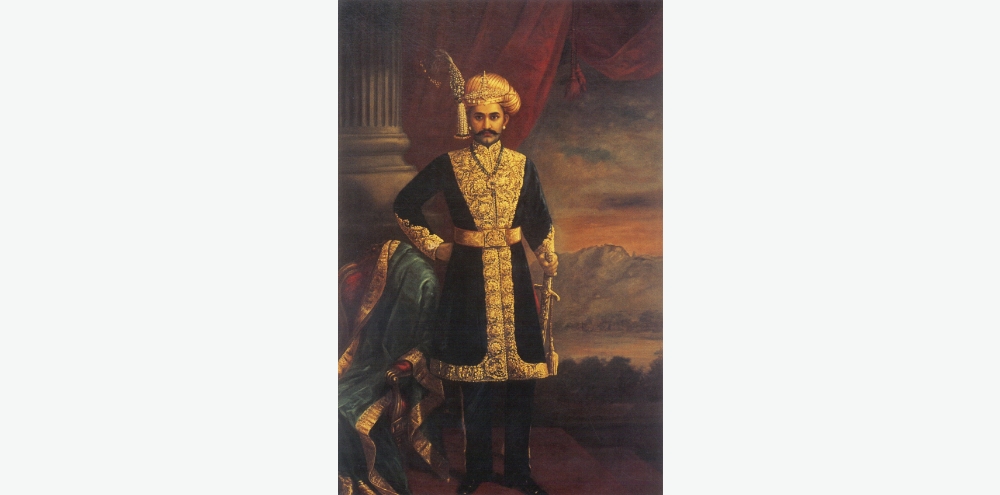

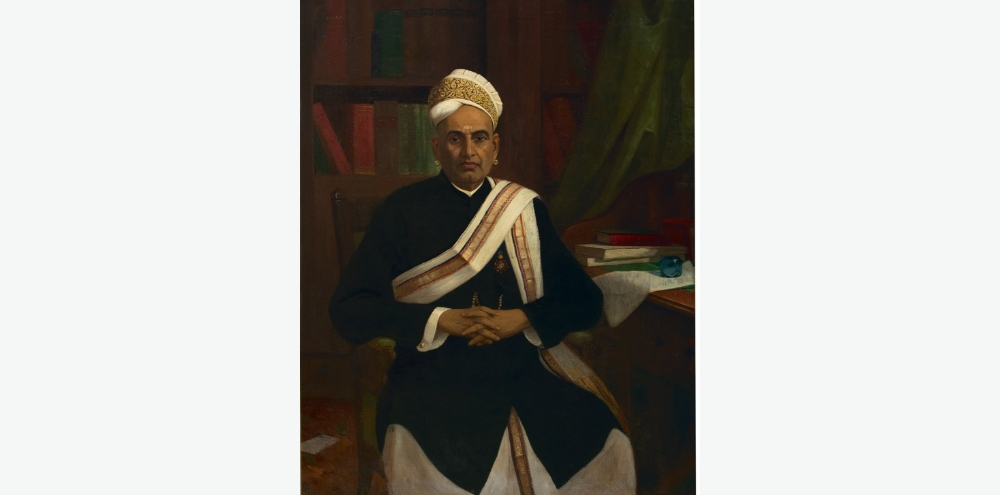

Art forms such as Mughal and Rajput miniature paintings from the 15th–18th centuries — which were made using water colours or pigments and held the Indian imagination for centuries — changed as a result of shifts in artistic patronage. The art schools set up in Indian cities introduced oil paints as the primary medium, and the first generation of artists in British India, who graduated from these schools, aspired for the same recognition as their European peers across the globe. Distancing themselves from indigenous art practices, they attempted to master the art of realistic and illusionistic oil painting to secure commissions for their portraits and gain entry to academic exhibitions that held great prestige. Oil-on-canvas paintings, particularly featuring portraiture, connoted affluence and began to make their way into wealthy Indian homes, initially to impress Europeans.

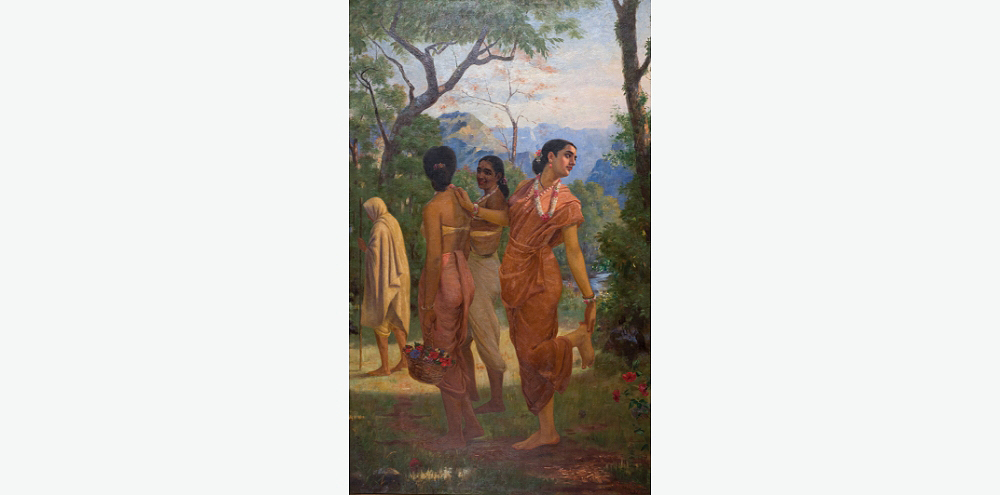

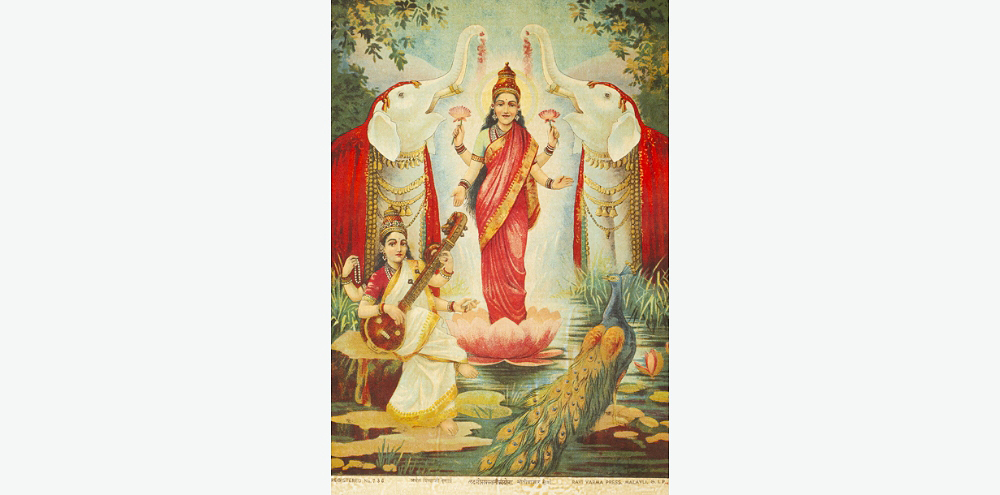

Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), in particular, embodied this new trend through his realistic oil paintings modelled on European techniques of illusionism used to simulate the optical reality of the viewer. Despite several paradoxes in his identity, particularly that he exemplified the stature of an academic artist without having ever gone to art school, he created the model of artist-as-entrepreneur in India. Ravi Varma was celebrated by the British and was popular among Indian rulers and the broader society. Alongside his painting practice, Ravi Varma also established a printing press in Bombay in 1894. This caused an important shift in the circulation of art beyond upper-class patrons, as the oleographs of goddesses and mythological narratives produced in his print studio were purchased by households across the subcontinent. While his works have had a long-term impact on Indian visual culture, it is worth noting that near the end of his life and career, with changing tastes and preferences, his reputation suddenly plummeted and his work was perceived not to be ‘Indian’.

Recognition of Artists

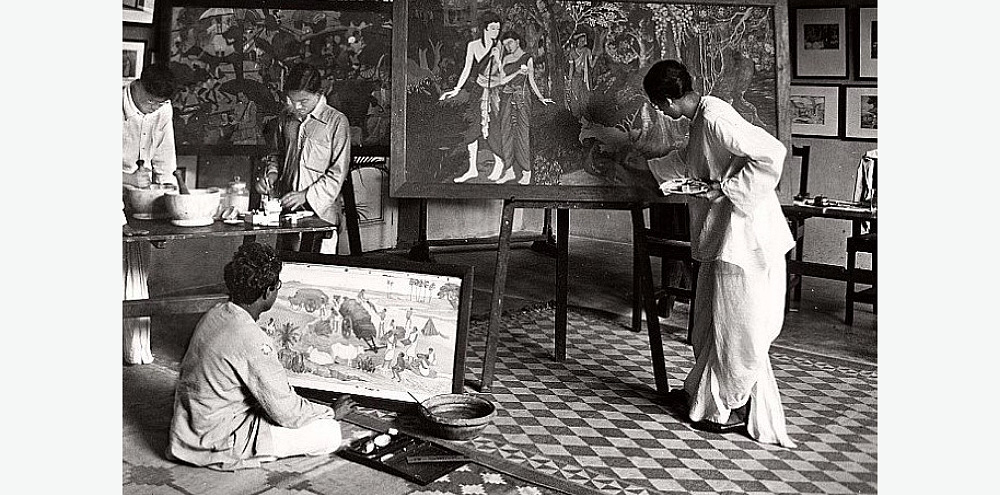

In traditional guilds, workshops or one-to-one apprenticeship models of studying art in India, students trained intensively under their teachers, who were often also their role models. Following their apprenticeship, they would work within their communities, or find employment in courtly workshops or ateliers. The university-based artistic training and the exhibition opportunities introduced by the British led to more artists receiving individual recognition.

With the stronghold of colonial rule in India in the 19th century, new perceptions of artists’ identity, new audiences and new methods of artistic production emerged, paralleling developments in the Euro-American world. On the one hand, art-making as a profession was now marked by social status, respectability, academic training and prospects of a lucrative career. On the other hand, only styles that were considered ‘high art’ fit within this new structure, relegating generations-old indigenous art traditions to the category of folk art. The establishment of this binary has had consequences that persist to this day, and later in this Course, we will look at ways in which we can dismantle and look beyond it.

Having set up some key contexts within the field of art in India, we can now begin to look at various ways in which these have established several norms, and also consider how artists – especially those who trained in colonial art schools – have reckoned with, resisted and challenged them. Many of these responses have been parallel to India’s freedom movement, and in the subsequent Topics of this Lesson, we will consider three distinct approaches to the idea of nationalism against this backdrop.

Providing a brief overview of the shifting systems of patronage and art practice in colonial India, this Topic introduces a number of new artists, institutions, styles of painting and more. Take a closer look at some of these through the following glossaries and articles!

- Mughal Manuscript Painting

- Rajasthani Manuscript Painting

- Raja Ravi Varma

- Raja Ravi Varma Press

- Oleography

- Sir JJ School of Art, Mumbai

- Government College of Fine Arts, Chennai

- Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata

Further Readings