The Decline of Handlooms: From Handmade to Factory Made (tbc)

Lesson Goals

- Introduce learners to the establishment of India’s very first cotton mills in Bombay, and the subsequent industrialisation because of them.

- Cotton changed the nature of the city leading to several socio-cultural and economic advancements.

- Familiarise readers with the visual culture and architectural progress that took place in Bombay — egged on by cotton money — by visually analysing particular photographs, buildings, trade tickets, etc.

- Introduce the learner to nuanced ideas such as unfair labour practices, slave trade etc that came along with industrial progress both globally and within the Indian context.

- Introduce learners to the cotton strikes, one of the biggest and most organised labour movements of its time.

Introduction: Colonialism, Industrialisation and Cotton

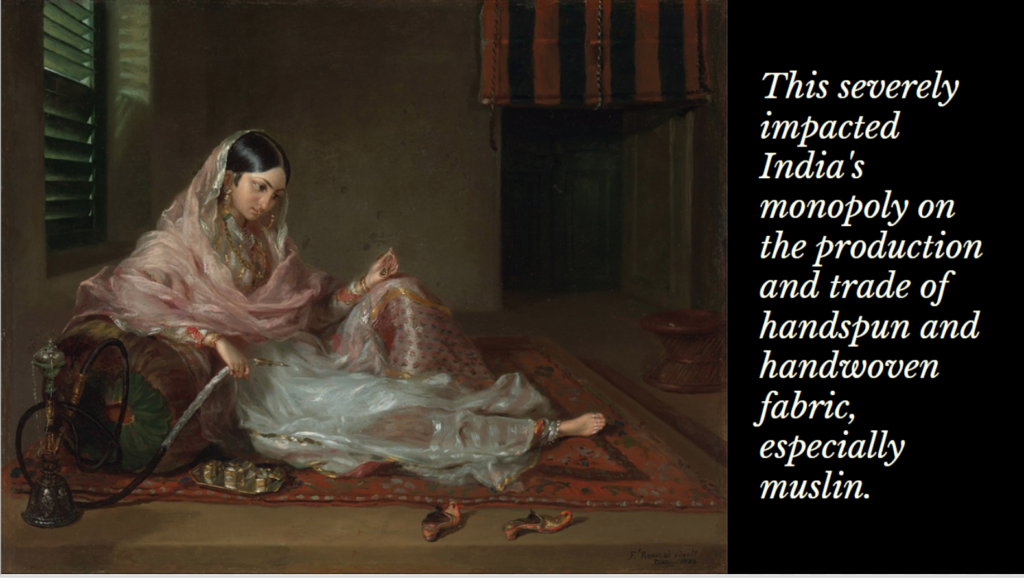

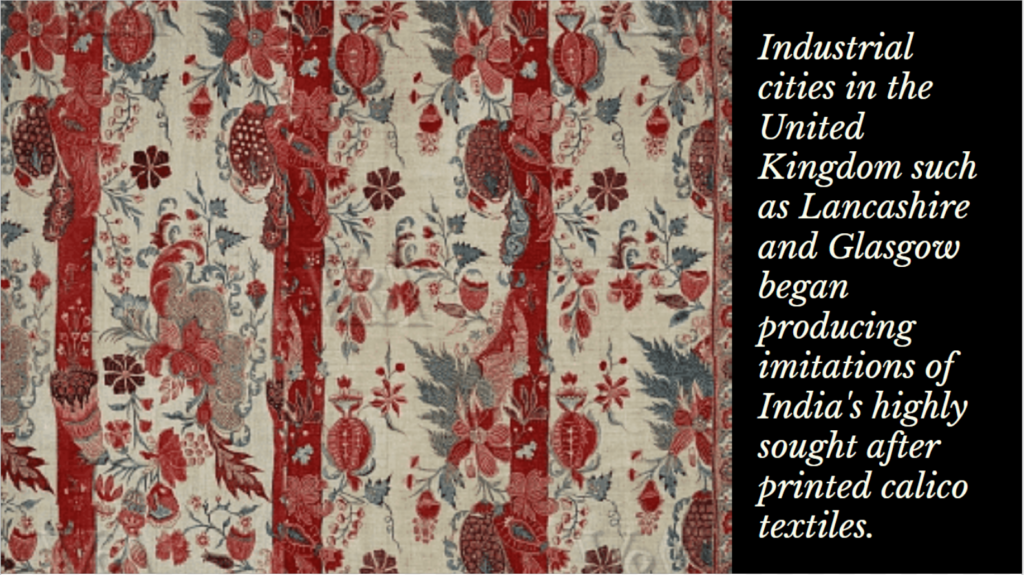

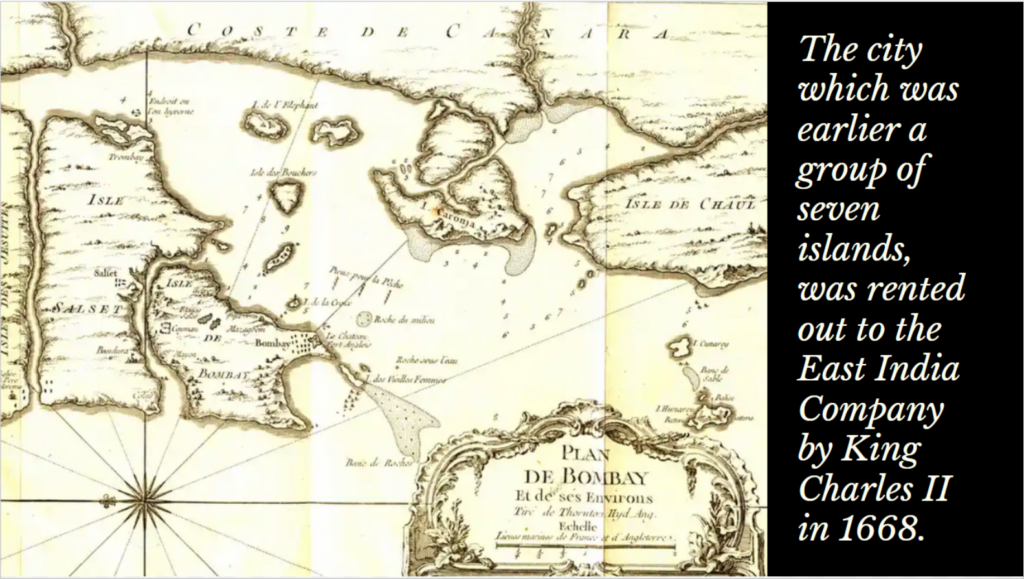

In previous lessons, we discussed how dyed and printed cotton textiles from India have been revered for millenia. By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch and British East India Companies had taken over India’s historic textile trade. Trade in India textiles was highly profitable for the East India Companies due to the popularity of Indian cottons and chintz in European markets. As a result of the profits gained from this trade, the British had political impetus to conquer large parts of India. India’s colonial period began with the British East India Company’s victory at the Battle of Plassey (1757). The British political administration in India further intensified from 1857, after which time India was directly ruled by the Crown.

Against a backdrop of progressively languishing handloom industries in India with the onset of industrialisation, and a rise in global demand for raw cotton, businessmen in India began to start their own industries for cotton manufacturing. These industries propped up in urban areas of the country like Ahmedabad, which came to be known as the ‘Manchester of India,’ — where the prominent Shahpur mill opened in 1861, and the Calico mill in 1863 — Calcutta, and Bombay, which is a prominent example where this industry has had an enormous influence.

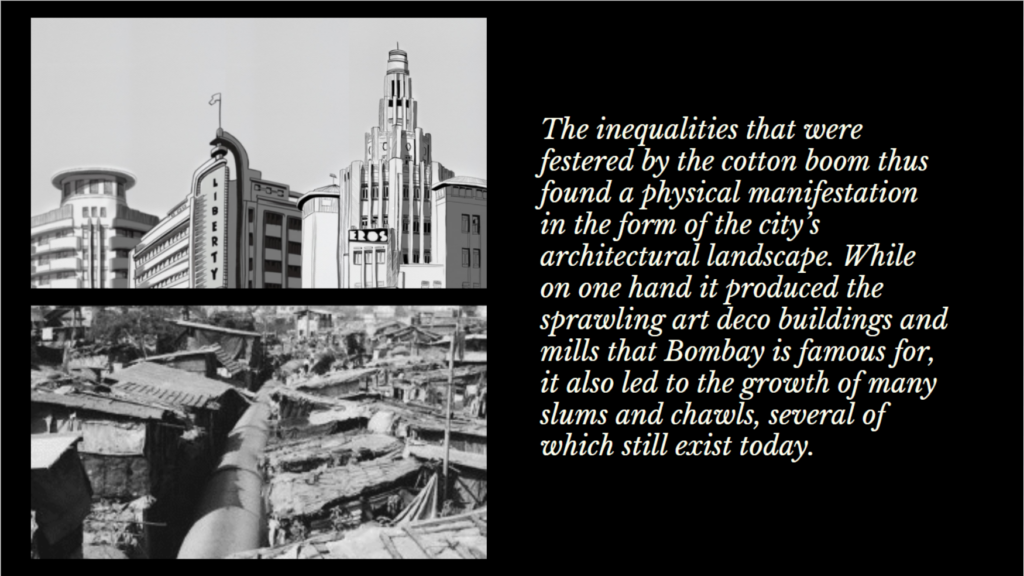

This lesson will look at how this development of cotton manufacturing laid the ground for Bombay’s architectural, cultural and socio-political development, resulting in the city becoming India’s largest metropolitan city and financial capital. However, even with all these advancements, there was a darker side to industrialisation that took the form of a stark socio-economic bi-polarity that exists even today. We will address this in the lesson through questions of labour and politics.

Bombay’s “White Gold” – Cotton in the city

In 1854, Cowasji Nanabhai Davar established one of India’s first cotton mills in Bombay (now Mumbai), ‘The Bombay Spinning and Weaving Mill.’ Although mills were established in other parts, it was in Bombay however where the largest number of mills flourished.

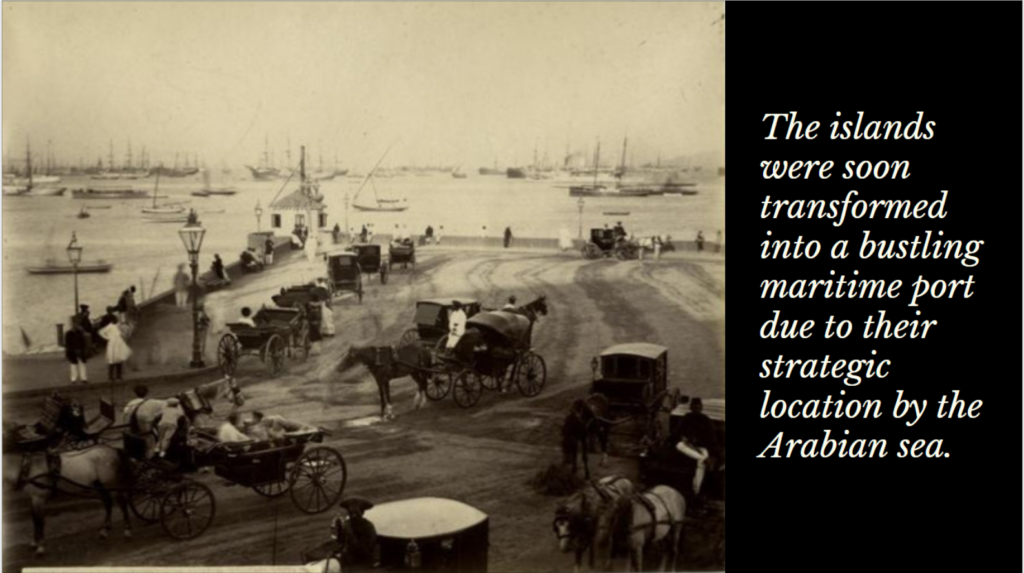

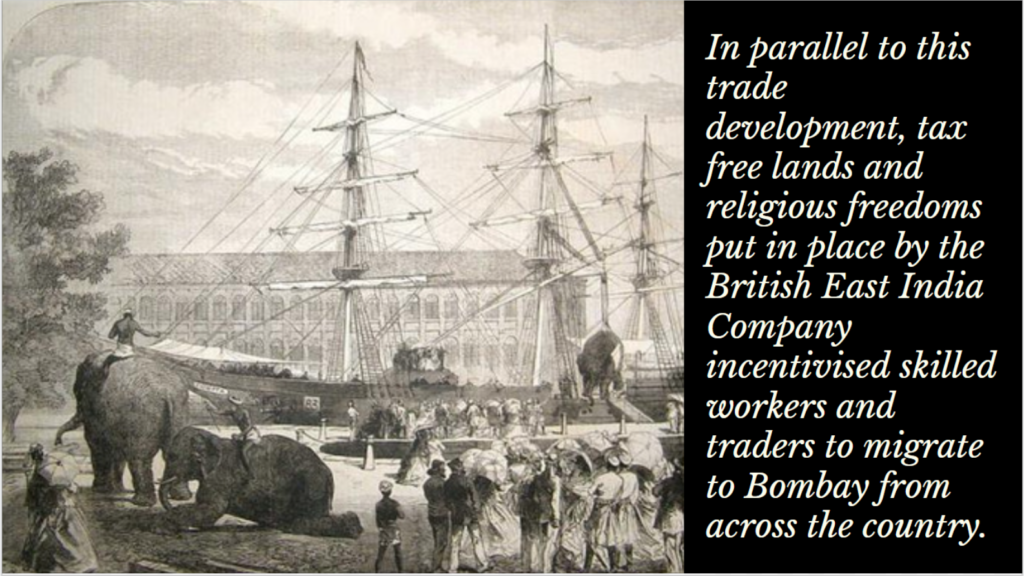

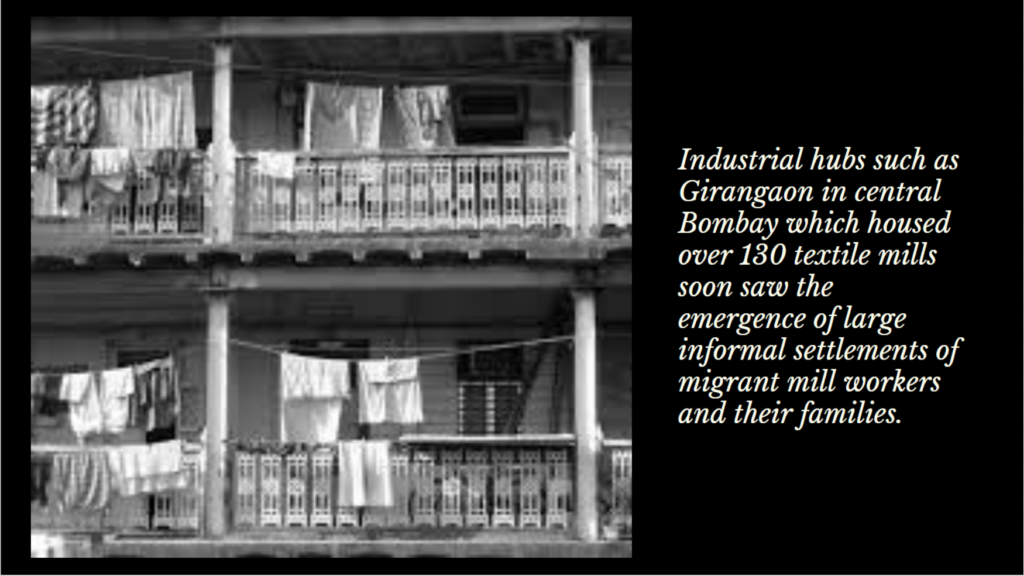

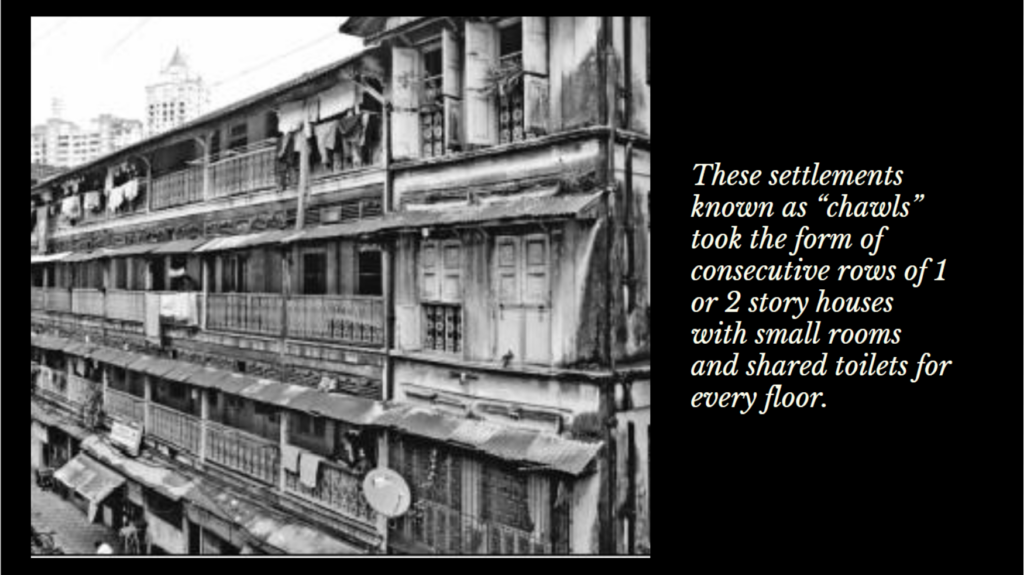

The construction of docks here enabled goods to be exported to Europe, the US, China, and Japan. In parallel to this trade development, tax-free lands and religious freedoms put in place by the British East India Company incentivised skilled workers and traders to migrate to Bombay from across the country. Bombay became a natural choice for industrialists to establish cotton mills. In addition to being a trading hub, the city was well-connected to cotton-growing districts through the transpeninsular railway network set in place in 1854.

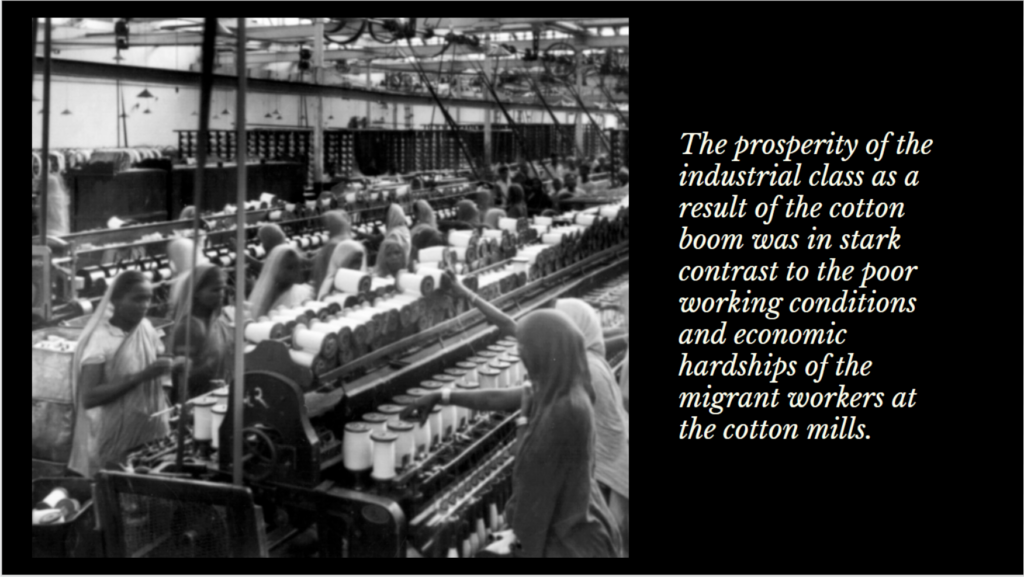

The city further saw a “cotton boom” in the mid-19th century that boosted its expansive industrial growth. In this cotton boom, Britain — which earlier exported raw cotton from the US — started to export large quantities of cotton from Bombay. This was due to the ongoing Civil War in the US between 1861 and 1865. Due to the increase in exports of cotton from Bombay to Britain, there was an influx of money in the form of profits to merchants, bankers and traders who invested in cotton exports. These factors not only boosted the growth of Bombay’s mills, but also contributed to the city’s transformation from a trading to a manufacturing hub.

In addition to architectural advances, there were also visual developments that came out of the cotton boom in Bombay at the time.

Cotton mills and Labour Practices

Note

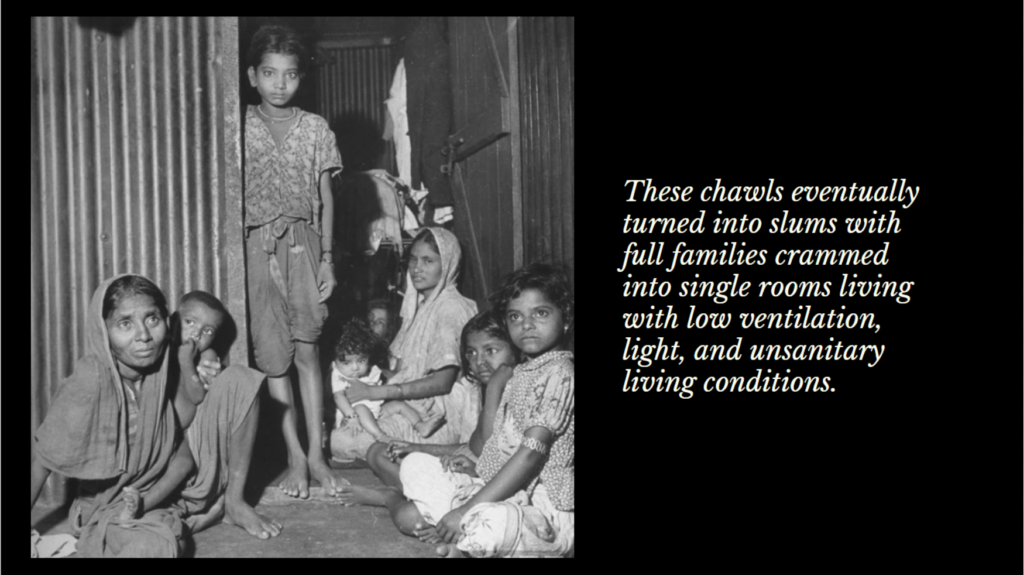

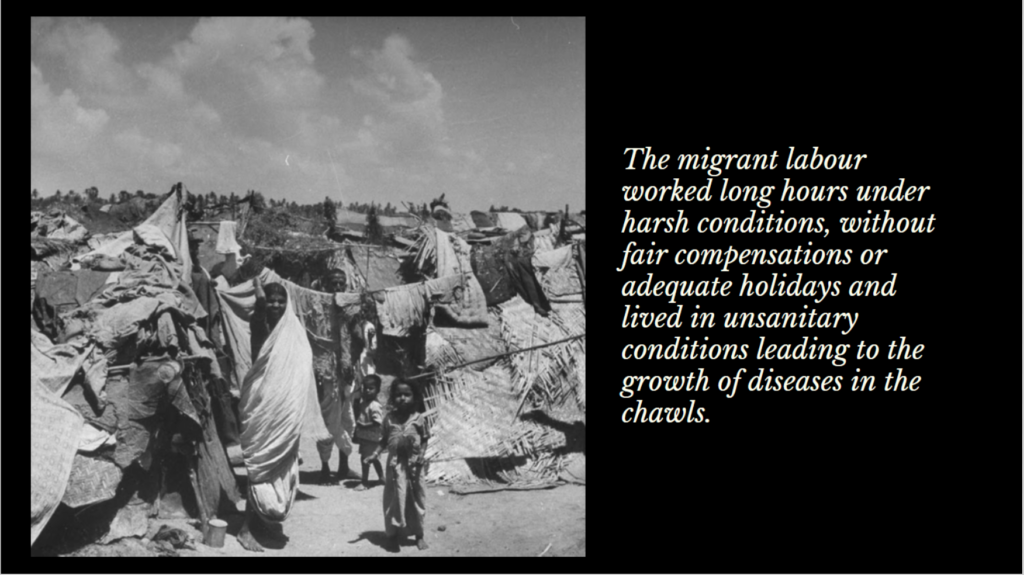

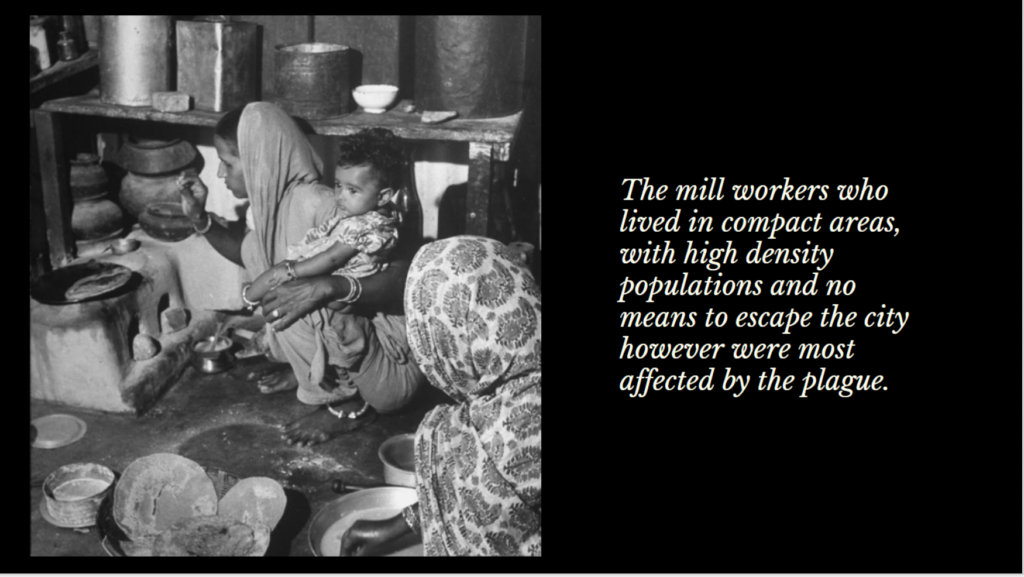

Although the living conditions were squalid, the slums developed a rich cultural and social life at the time. Due to space constraints in their living quarters, people regularly collected in common areas. With a varied fusion of migrants from different regions of the country, life in the slums was rich in cultural diversity. People celebrated distinct Hindu and Muslim festivals together and patronised various forms of poetry and theatre.

Having learnt about the adverse living and working conditions of cotton mill workers in Bombay, let us have a quick look at how the demand for Indian cotton played a larger role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade in the mid-18th century — with Bombay being one of the chief ports of embarkation for this trade. Indian cotton formed a large part of the African imports from Europe throughout period of the Atlantic slave trade — which involved the transportation of enslaved people from various African countries on the Atlantic coast mainly to the Americas.

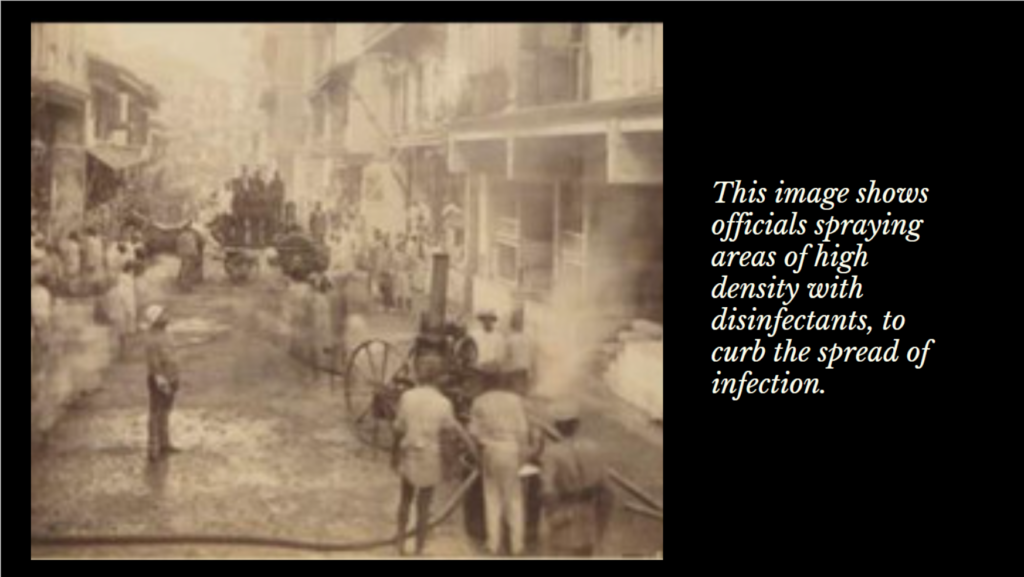

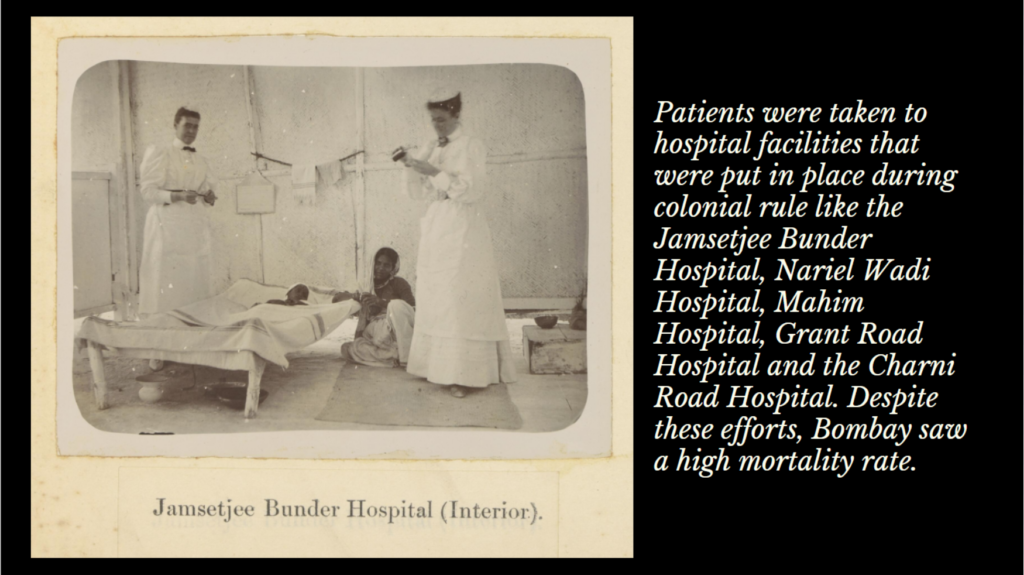

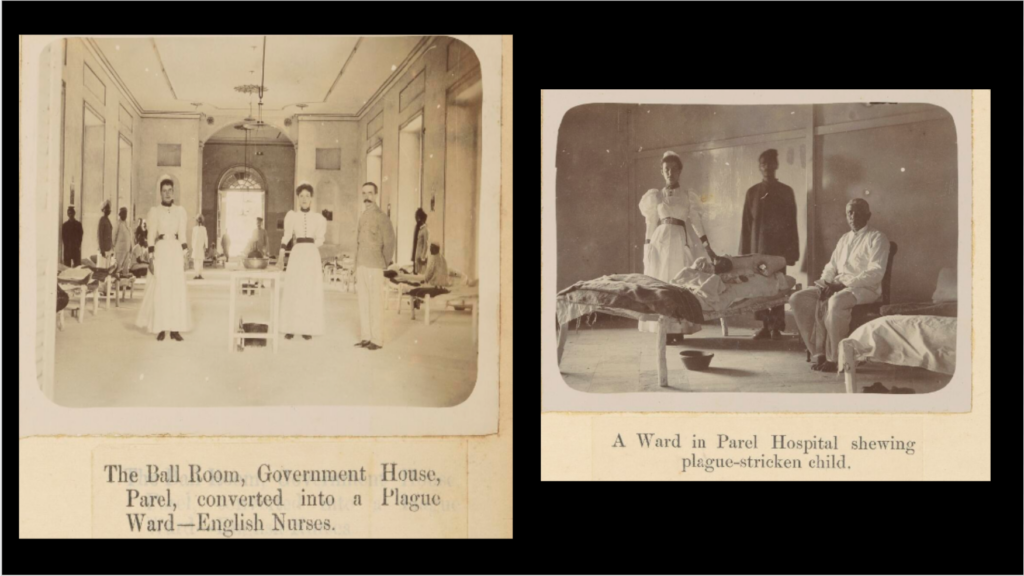

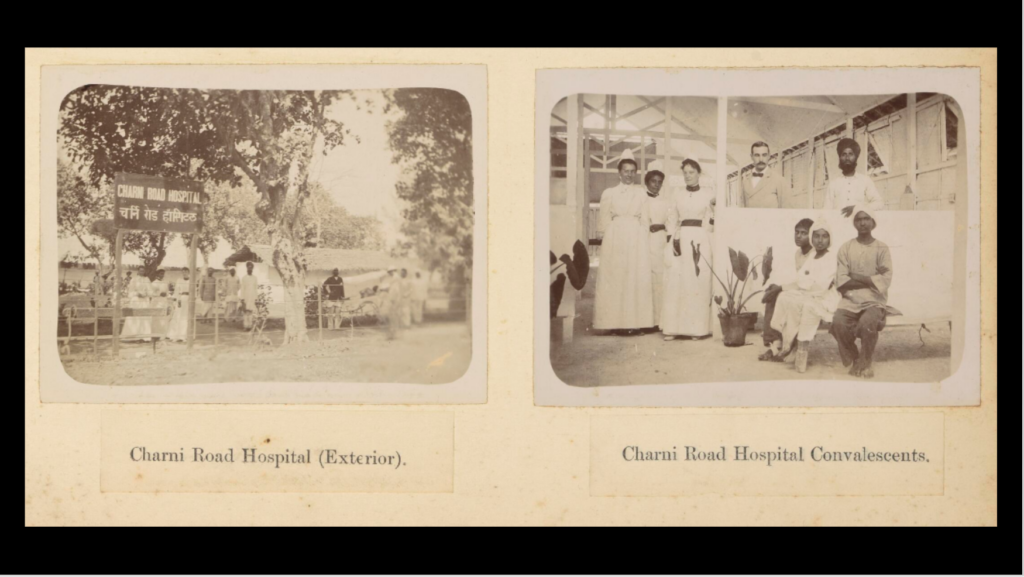

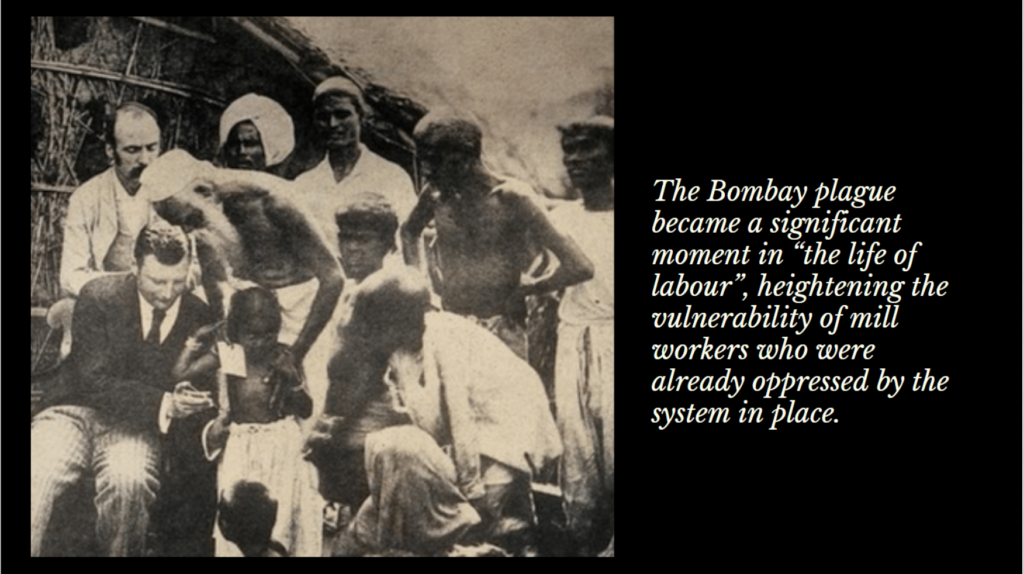

Bombay, as we have come to realise, was a melting pot of cultures and activity. Bombay’s success and it’s soaring growth however came to a brief halt however when the infamous Bombay plague (1896-1897) ravaged large parts of the city at the end of the 19th century.

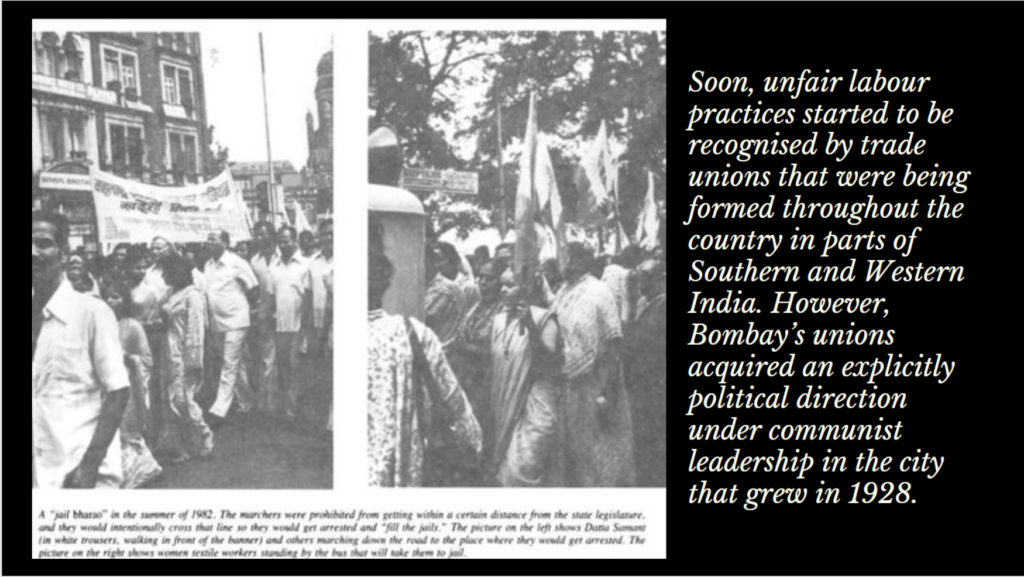

Although India gained independence from British rule in 1947, factory workers were still working under draconian policies introduced during the colonial era, with little regard for their rights. Pressure mounting from nationwide agitation against the British in the years leading up to 1947 culminated in a series of strikes that lasted for a period of 18-months, which started in 1982, eventually crippling the functionality of Bombay’s textile industry. The strikes act as a significant moment in the history of Bombay. It is seen as a turning point in the life of labour, changing employment patterns in the city. After the strikes, the city became a financial hub instead of an industrial one.

As is evident in Bombay being referred to as the “Financial Capital” of India. The strikes not only changed the consumption and manufacturing patterns of the city but also changed the landscape of Bombay. After a period of remaining derelict, many of the historic mills that transformed Bombay’s character as we know it were redeveloped soon after.

The mills still act as an integral part of Bombay, both structurally and visually and have served as a foundation for many contemporary development projects which have taken the form of recreational units like shopping centres, malls and luxury real estate properties.

The rise of the urban proletariat and the strike that followed inspired many works of art by artists, poets and authors. One artist in particular, Sudhir Patwardhan has worked on themes relating to the plight of mill workers from the mid-1970s. In his painting Lower Parel (2001), the artist depicts this area where the erstwhile mills were located. In his post-strike depiction of the urban landscape, he shows the now defunct factories surrounded by new small scale shops and luxury high rise apartments — invoking a sense of gentrification the area went under after the strikes ended and the mills shut down.

Narayan Surve’s revolutionary Marathi poetry also served as a beacon of hope and revolt of the time. Having grown up working odd jobs in the mills, Surve has a firm grasp on working class relationships. Surve and Pathwardhan collaborated in 2018 to create ‘Saacha The Loom’ a film that captures the changing nature of Bombay. Through Surve’s poetry, Pathwardhan’s paintings and interviews with the two, the film looks at how the city — once a hub for the political insurgencies of the proletariat — has removed all traces of the strike from it’s fabric. The film made its debut at the Kochi Biennale, a bi-annual festival that takes place in Kochi, Kerala. It is now a part of “Giran Mumbai”, a webarchive of photos, texts and audio-visuals that act as an ode to the people that formed industrial Bombay, the struggles they faced and their contributions to the cultural fabric of Bombay. Even today, the strike has inspired a significant cultural output in terms of films, plays, and other forms of art. Films like Bombay Velvet (2015), by noted director Anurag Kashyap have been inspired by the Bombay Mill Strike.

Conclusion

The century that followed from the inauguration of India’s first textile mill, saw a huge number of changes. There were two sides to the rapid industrialisation Bombay underwent in the 19th century. On the one hand, industrialisation in the city led to immense infrastructural and cultural development. On the other hand, there was the emergence of an economic bi-polarity with the rise of the business merchant class and labour working class that lived and worked in astonishingly contradictory positions, a phenomenon which still plagues the city today.

Furthermore, the transition from handmade cloth to mill made production affected the handloom industry drastically. In the 1930s, social concerns caught up with the industrial progess reached through mills, which are reflected through a nationalistic push for handwoven and handspun and nation-wide agitation of workers.

Notwithstanding the negatives however, factory workers and artisans have been equally important in the production of India’s cotton cloth, there were now two types of labour that depended on textiles for their livelihood. Even though the Bombay mills shut down, India is a major manufacturer of cotton, with cotton cloth leading to a large part of India’s exports. In the following lessons, we will discuss the importance of India’s textile traditions in India’s journey towards independence, and the consequences it faced after its freedom.

Bibliography: