Art Museums in India, Private and Public

In India, the emergence of museums can be traced back to the colonial period. These followed in the footsteps of European institutions such as the British Museum in London or the Louvre Museum in Paris, which opened their doors to the public in the late 1700s. The earliest Indian museums were also tied to the politics of colonial patronage and knowledge production, often focussing on anthropological inquiry, archaeological finds, craft forms and artists studying at colonial art schools. At the same time, Indian patrons, particularly rulers of princely states such as Sayaji Rao III Gaekwad of Baroda in Gujarat, western India, embarked on their own museological initiatives, displaying their private collections, and funding archaeological excavations and the conservation of monuments.

In the decades following independence, the task of building or running a museum of art shifted to represent the diverse regions and histories of the country. The challenge was also to reinvent and reassess the obsolete and sometimes problematic systems and displays of colonial museums to meet the needs of a new public. Today, museum infrastructure in India takes two forms – public museums that are founded and run by the government and private museums established and run by individual patrons. In this Topic, we will look at examples of each of these and how they have created spaces for discourse.

Let’s begin with Mumbai’s oldest museum, founded during the colonial period, and revived in recent decades as an important public institution.

Decolonising and Democratising Art: Dr Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum

The Dr Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum first opened in 1857, and since 1872 has been located at its present site — adjacent to a botanical garden and zoo, Rani Baug — in the diverse area of Byculla. Initially called the Victoria and Albert Museum, conceptualised as a counterpart to London’s V&A, its focus was to share the erstwhile Bombay Presidency’s cultural and economic history through objects from the 19th and 20th centuries. Its permanent collection includes works of art and craft, as well as dioramas, maps, lithographs, miniature clay models and rare books. In 1975, nearly a generation after independence from Britain, the museum was renamed after Dr Bhau Daji Lad (1824–1874), the first Indian Sheriff of Bombay, a philanthropist, historian and physician. Dr Lad was also the first secretary of the institution’s committee.

Over the years, the Museum fell into disrepair, and in 2003, under the leadership of Honorary director Tasneem Zakaria Mehta, it underwent a unique shift through a public-private partnership between INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage), the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation and the MCGM (Municipal Corporation Greater Mumbai), which worked together to restore its building and objects. Since this major and transformative exercise, and through Mehta’s continued role as director, the Museum expanded to present contemporary art through solo exhibitions of leading artists and wider programming for all audiences. The Museum’s location, its affordable ticket prices, and programme have made it a beloved institution for the people of Mumbai, and it boasts a footfall of up to 5,000 visitors on most days.

While the museum’s permanent display highlights its historic collection, special exhibitions here have featured contemporary Indian artists who engage closely with the complex history of colonisation and related contemporary issues in the city, which the museum is steeped in. Some of these exhibitions have been in partnership with other institutions and multinational corporations like the Italian luxury brand, Ermenegildo Zegna’s ZegnArt. For instance, in 2013, as part of the ZegnArt Public initiative, the Mumbai-based artist Reena Kallat (b. 1973) was chosen for a large-scale commission on the museum’s facade. Her project, Untitled (Cobweb/Crossings), was composed of a web of 550 rubber stamps joined by steel rope, with each stamp bearing a colonial street name in the city that has been replaced by a vernacular name. Reflecting upon the renaming of cities, streets and institutions, such as the Museum itself, which have been a part of decolonisation efforts in India, the work invited considerations of how the history and identity of the city have been altered over time. Furthermore, presenting the work on the building’s exterior invited a rare opportunity for public engagement.

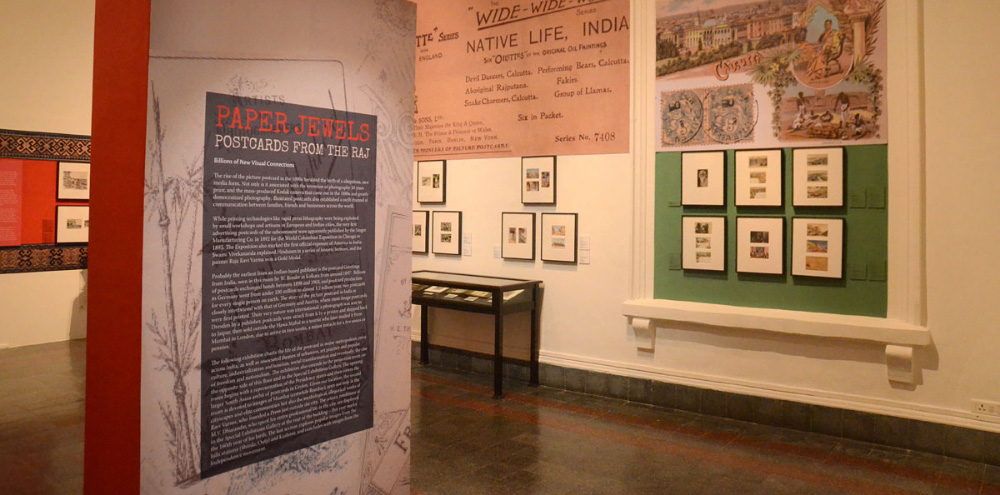

More recent projects at the Museum have also looked at lesser-studied collections and artists integral to Indian visual culture and art history. These include an exhibition focussing on postcards from the British Raj, which looked at how the network of the postcard went beyond literal connections to urbanism, tourism and visual culture, and was integral to the rise of freedom and nationalism in India. Another show focussed on MV Dhurandhar (1867–1944), an artist whose career closely chronicles India’s late colonial period in the early and mid-20th century. Dhurandhar studied and worked in Bombay, and his work was made in the academic realist style, which was favoured at the time. It reflected the vision of the push for independence coupled with humour and the body language of theatre, as the artist had a close relationship with a renowned theatre performer, Balgandharva. In addition to these, the Museum has also hosted solo exhibitions showcasing works by artists such as Atul Dodiya (b. 1959), Dayanita Singh (b. 1961) and Rohini Devasher (b. 1978) among others, as well as thematic group exhibitions focussing on subjects ranging from perspectives on textile practices to environmental concerns.

The Dr Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum’s programme not only reflects on its own complex history as a colonial-era institution but also engages actively with present times. As a case study, it showcases the potential that public museums have in developing critical programmes that engage with wide audiences in a variety of ways.

It is important to note however, that most public institutions in India face challenges such as low funding, poor infrastructure and bureaucracy. It is especially in light of some of these issues that we might turn to private museums in the country, which can often realise large-scale and more ambitious projects.

Let’s look a little more closely at one example of such an institution.

Local and Global Collaborations: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

The pioneering vision of art collector Kiran Nadar led her to establish the first private museum dedicated to modern and contemporary art in India, with its inaugural exhibition taking place in 2010. The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) was founded within the Shiv Nadar Foundation, a matrix of diverse educational philanthropic initiatives, and has been temporarily based in two sites in Delhi until its permanent building is anticipated to be completed in 2025. While the private museum began with the intention for Nadar to share her personal art collection with the broad public, its vision and ambition have grown, addressing the lack of institutional spaces and opportunities for education, community building and dialogue around culture in India.

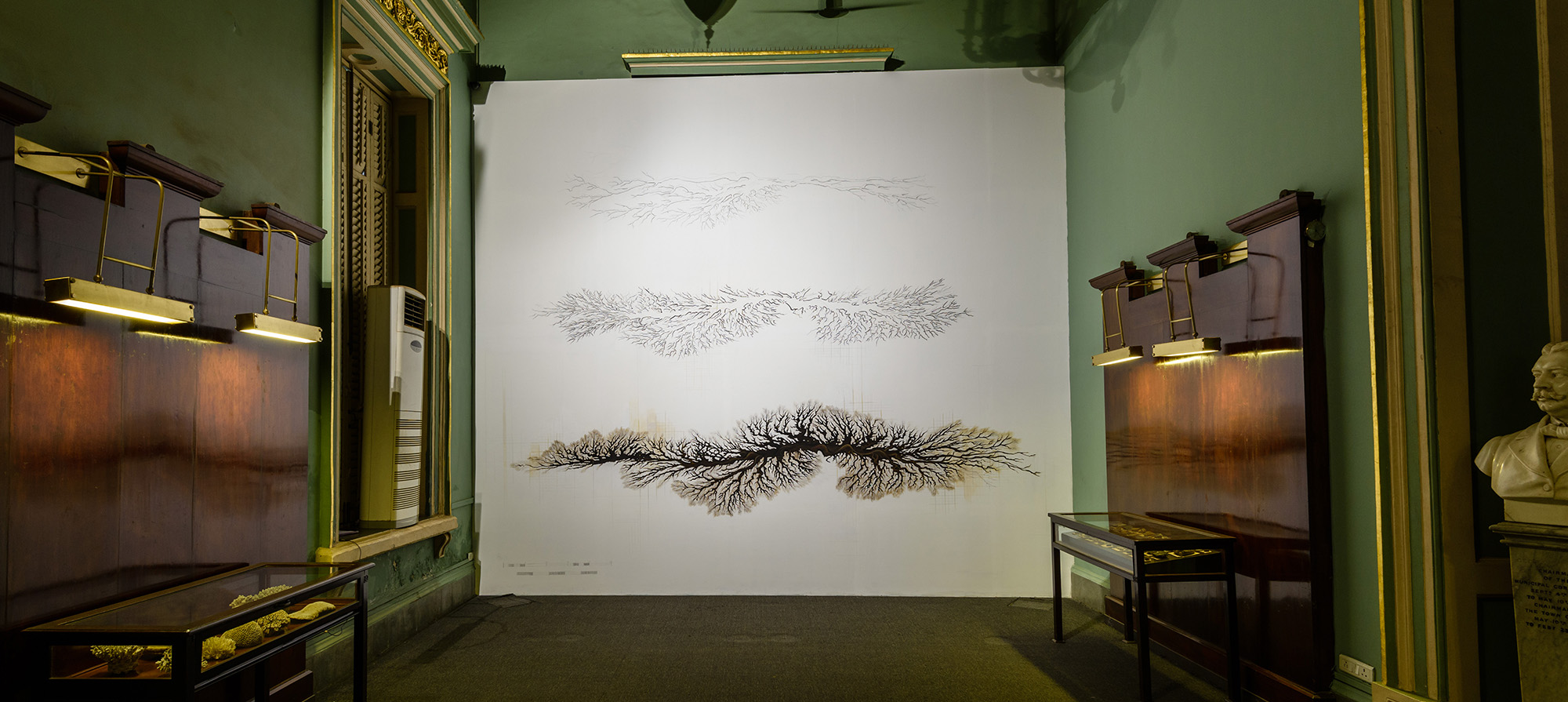

Following a series of initial group exhibitions that introduced the Museum’s collection and many modern and contemporary Indian artists to the public, over the past 12 years and in partnership with leading global institutions, KNMA has hosted a number of major solo exhibitions focussing on key Indian artists. For example, a presentation of work on Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–1990) organised by the Museum’s Director and Chief Curator Roobina Karode was one of the inaugural exhibitions at the Met Breuer — a temporary branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) in New York and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2015–2016. Karode and the KNMA also collaborated on two exhibitions of Jayashree Chakravarty’s (b. 1956) work in France in 2016 and 2017, with presentations at the Musee Départemental des arts Asiatiques in Nice, France in 2016–17 and at the Musée Guimet in 2017–2018.

In 2019, the KNMA collaborated with the Ministry of Culture, the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) and the Confederation of Indian Industry, to organise the India Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale – one of the oldest international exhibitions held in the world. Celebrating Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th anniversary, this pavilion featured works by prominent Indian modern and contemporary artists such as MF Husain (1915–2011), Jitish Kallat (b. 1974), Atul Dodiya, Shakuntala Kulkarni (b. 1950), GR Iranna (b. 1970) and Nandalal Bose (1882–1966), among others. Each of these artists has reflected on a variety of themes related to Gandhi’s life, his philosophy and what he stood for in India’s freedom movement.

The exhibitions that the KNMA has organised have been critical in broadening access and a global context for certain Indian artists, and also in establishing the cultural capital and importance of the Museum itself.

Although the establishment of museums in India is tied to a complex colonial past, as we have seen, these institutions can play a vital role in serving as sites for disseminating culture and education. While a majority of public museums continue to have barriers to entry that prevent diverse individuals from visiting, private institutions like the KNMA have aimed for Indian art to be represented locally as well as on global scales. Through the examples we’ve looked at in this Topic, we’ve also seen how institutions often work in collaboration with each other to realise broader visions.

Despite the opportunities that museums present when it comes to providing a platform for showcasing art as well as educating audiences, it is important to think through who has access to such spaces (mostly located in urban areas) and which artists are afforded the opportunities to be exhibited in these spaces. Often the choice of artists represented here may reflect canonical biases that we learnt about in the previous Lesson, but many institutions and individuals are working towards creating more inclusive spaces.

This Topic looks at the histories of some important spaces that house, engage with, and display modern and contemporary art. To find out more about them and the works of similar institutions in the country, check out the following links.

- Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

- Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum

- Tasneem Zakaria Mehta

- Reena Saini Kallat

- Nasreen Mohemadi

- Roobina Karode

- Piramal Museum

Further Readings