Artist Collectives: Shared Visions and Collaborative Practices

Since the adoption of photography and greater engagements with new mediums such as video, performance and installation art, artists have explored a variety of ways to stretch the boundaries of their own work. Such experimental and multi-media practices have involved moving across disciplines, engaging with audiences in novel manners, and giving rise to new possibilities for artistic collaboration.

As we have already seen with the Bengal School and the Progressive Artists’ Group, artist groups and formal associations have been key to the history of modern and contemporary art in India. Especially in the 21st century, there has also been a marked rise in collectives of two or more artists who share certain goals and ideals, whether formal and aesthetic, or social and political, working together for a unified vision. A key difference between earlier artist groups and contemporary collectives is that historically, artists may have been associated with a group but still created work under their own names, while collectives give up individual names and identities to contribute to a shared goal.

Let’s look at two major collectives in India.

Raqs Media Collective

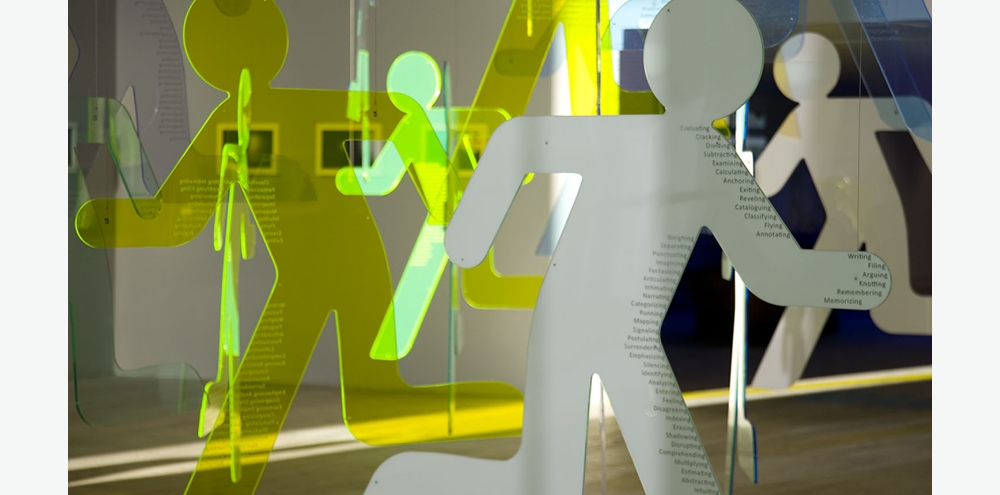

Founded in 1992, the Raqs Media Collective is composed of three independent media practitioners, Jeebesh Bagchi (b. 1965), Monica Narula (b. 1969) and Shuddhabrata Sengupta (b. 1968), who began working together after graduating from the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre at Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi. The name of their collective is based on the Persian, Urdu and Arabic word raqs that refers to the state of consciousness that dervishes — members of certain Sufi fraternities — attain through their meditative whirling. As an acronym, Raqs stands for ‘Rarely Asked Questions’, resonating with the Collective’s provocative explorations through their work. Raqs works across mediums ranging from installations, online and offline media objects, performances and encounters. Their practice also extends beyond producing art, as they work as curators, researchers and editors.

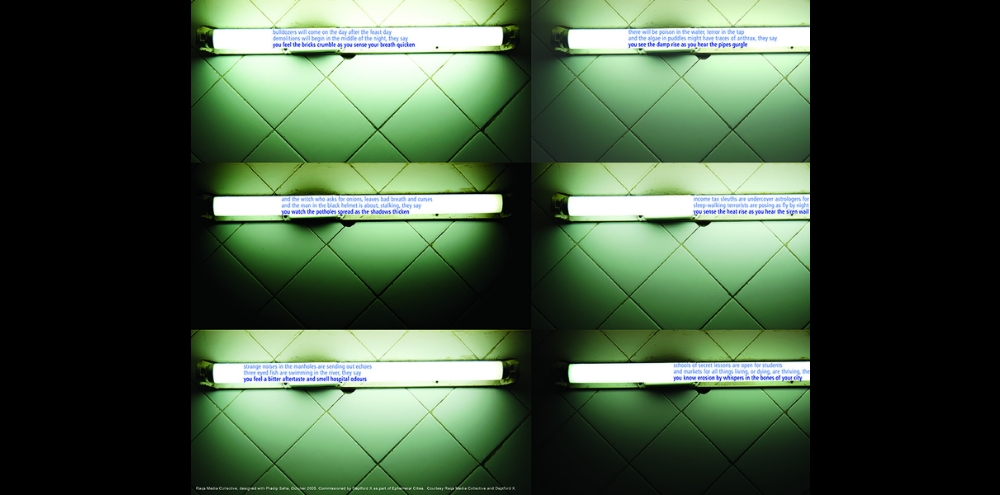

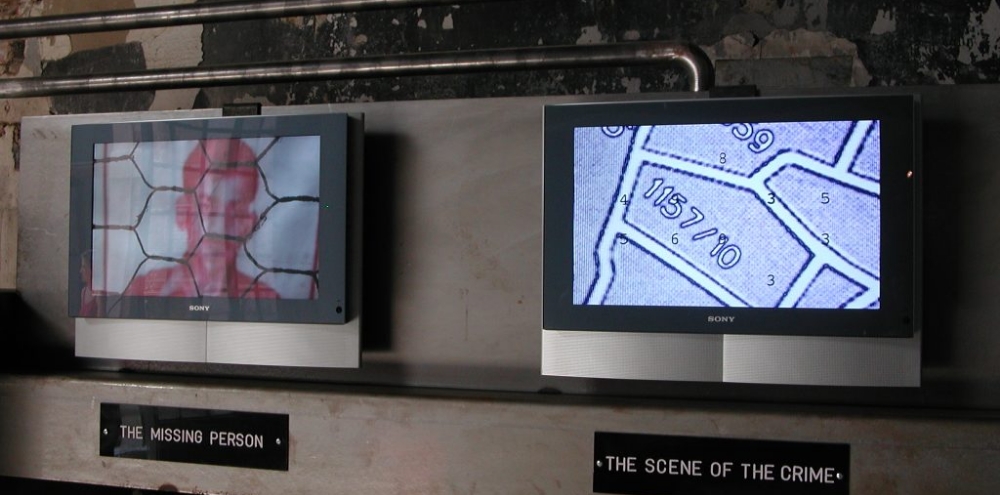

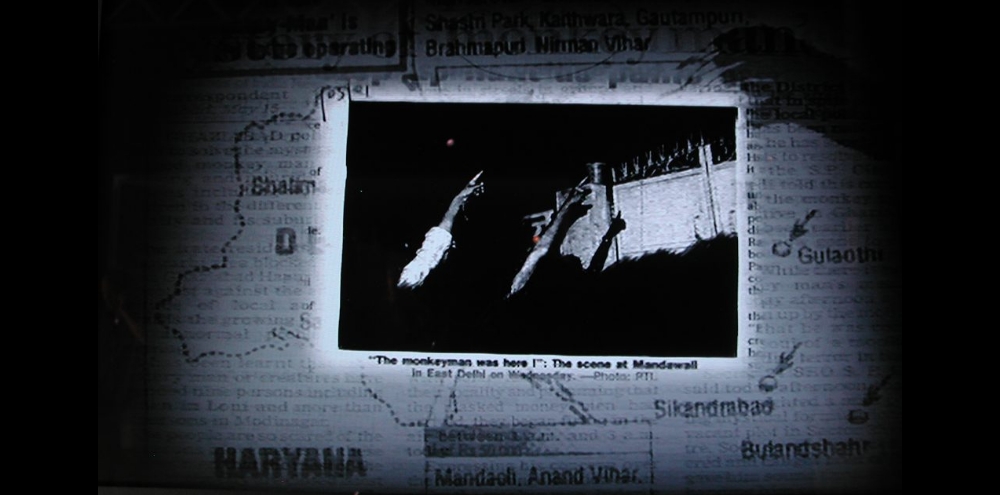

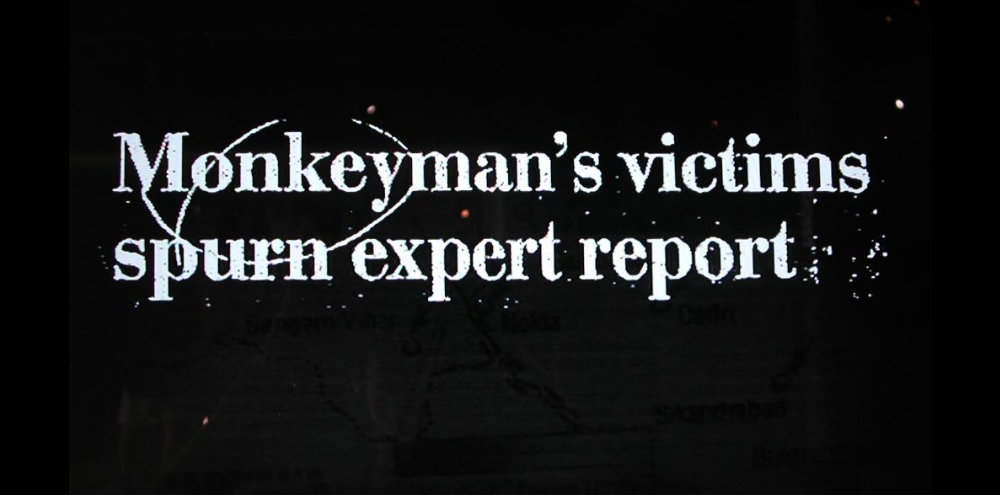

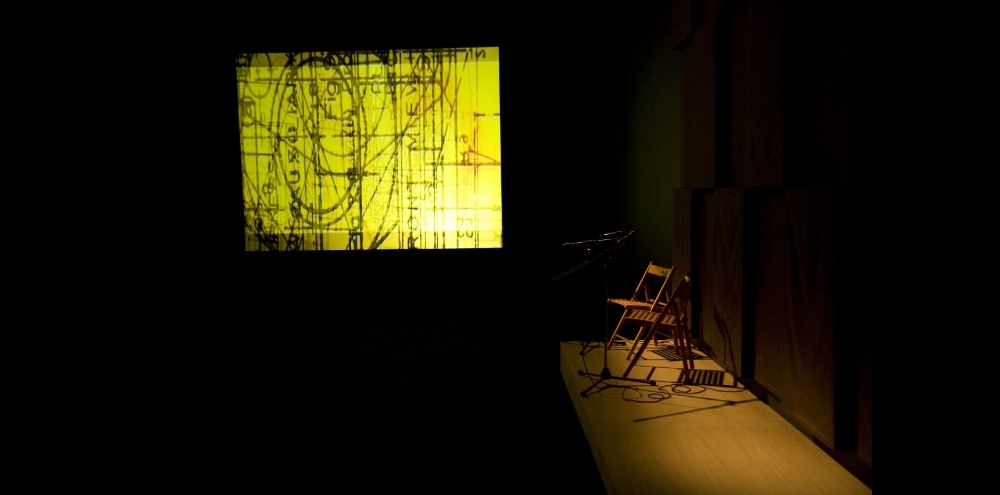

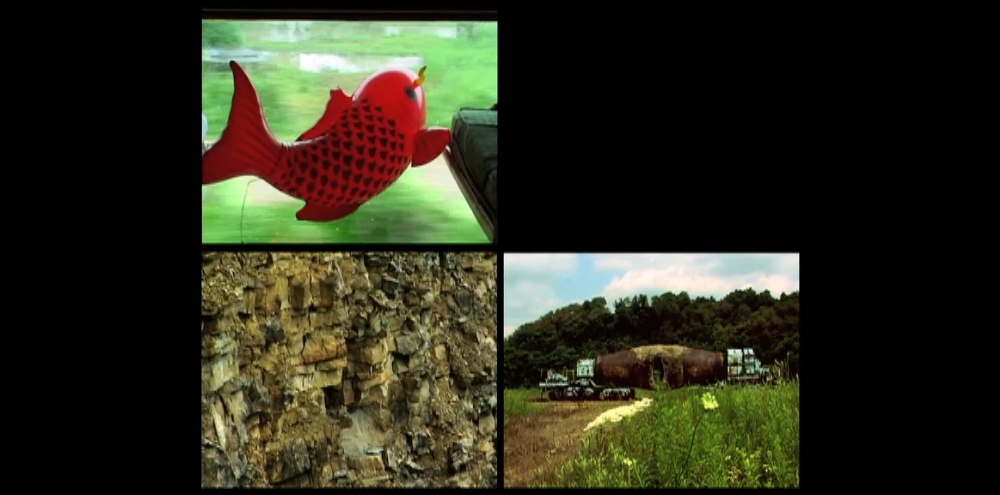

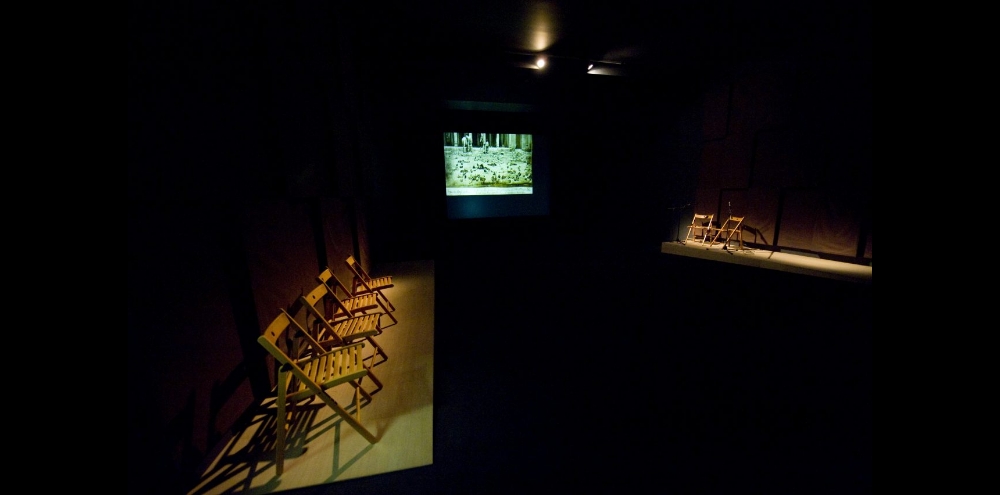

One of their seminal video installations, 5 Pieces of Evidence (2003), is a quasi-detective mystery work based on a 2001 scare that a ‘monkey man’ was roaming around a Delhi locality scratching the faces and haunting the dreams of people sleeping in that neighborhood. The work presents the city as a crime story with one aspect on each of its five screens, exploring different facets from ‘missing person’ notices to skyscrapers with the eyes of suspicious sleuths. The work reflects on urban development, migration and media attention, capturing Raqs’ ability to observe and comment on the mass hysteria of our times.

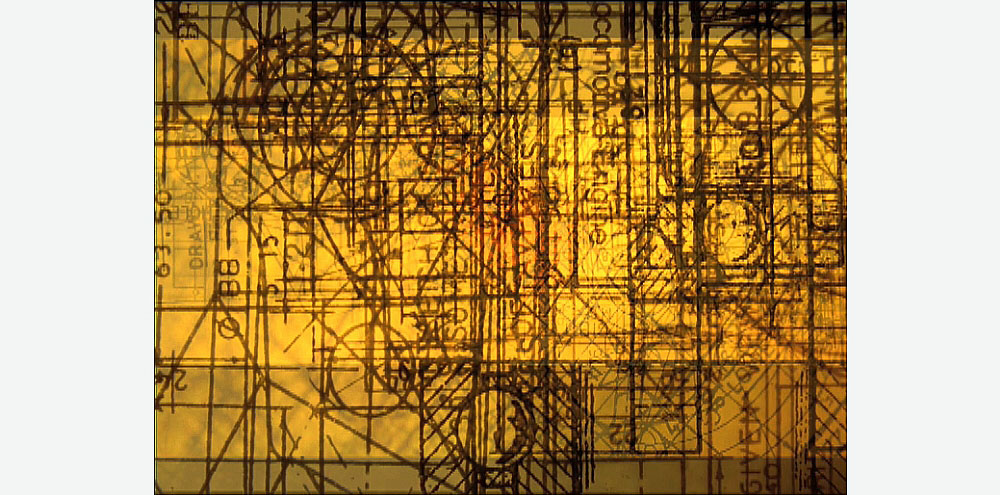

Other projects engage with history through archival materials, leaning on the collective’s work as researchers. For instance, The Surface of Each Day Is a Different Planet (2009) integrates historical photographs from the Galton Collection at the University College London and the Alkazi Collection of Photography to reflect on how ethnicity and race have been characterised. The work presents photographs of institutionalised individuals by 19th-century anthropologist Francis Galton, layering these with video footage of people moving from place to place. The work is intentionally open-ended, examining how collectivity and anonymity have been represented over time, and how identity is interwoven with attempts to reclaim agency in light of both colonial pasts and globalisation today.

Desire Machine Collective

Beginning in 2004, Sonal Jain (b. 1975) and Mriganka Madhukaillya (b. 1978) began collaborating as Desire Machine Collective. Like Raqs, their work and partnership as a collective has been socially and politically motivated. An instance of this is their conscious decision to shift their base from Ahmedabad to Assam in India’s north-east, following the 2002 bombings and subsequent sectarian riots in Godhra in Gujarat. Naming themselves after a concept in a seminal text by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Desire Machine Collective seeks to disrupt the ‘neurotic symptoms’ that arise from capitalism. Many of their projects have taken place in remote regions of India, and research and community engagement are important components of their work.

While their practice spans film, video, photography, sound and multimedia installations, the collective’s best-known work has in fact been Periferry 1.0, set on a a government-leased ferry docked on the Brahmaputra river in Guwahati. Periferry embraces nomadism, cultural exchange and the constant flow of the surrounding river that serves as a site of migration at the crossroads of south and south-east Asia. It creates a space for negotiating contemporary cultural production, including hosting formal artistic interventions or broader community events for people to engage with in their own ways. In using a boat as the setting for this network and exchange, the work engages with the long history of steamboats as an important source of transportation, especially for the trade of tea beginning in the British colonial period.

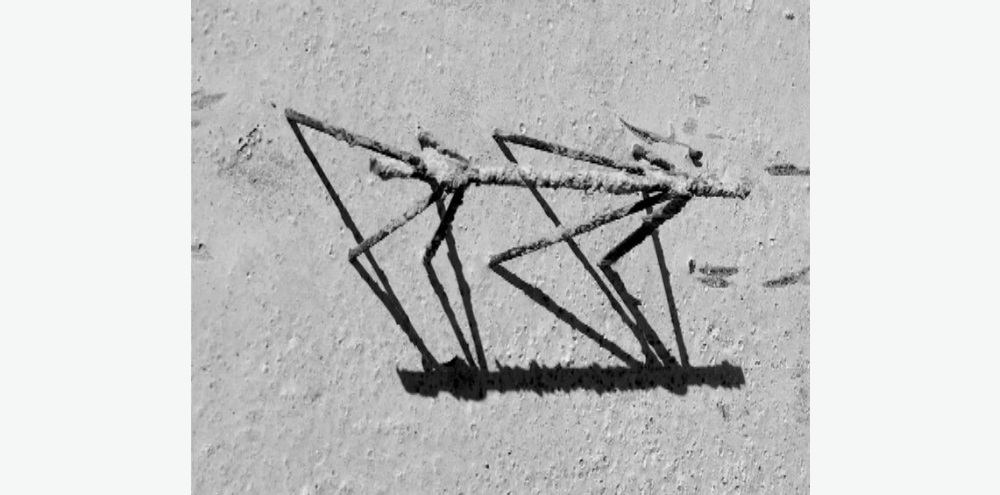

Their video works such as Nishan I and II (2007-2019) have also considered abandoned and contested sites, in the form of meditative video installations shot in Srinagar, Kashmir. Nishan is a slow reflection of time and space that takes place in a derelict apartment. The work integrates footage and photographs of everyday life in the city from an abandoned house that later became a bunker, reflecting the inherited traumas related to the history and ongoing conflict in Kashmir.

Desire Machine Collective has pointedly addressed various conditions and sites across the Indian subcontinent, ranging from Gujarat to Assam to Kashmir. With that, they’ve made a conscious choice to embrace the periphery rather than major urban art centres, which also allude to the title of Periferry.

The innovative practices of artist duos or collectives, such as Raqs Media Collective and Desire Machine Collective, have left a lasting impression on contemporary Indian art, reflecting on a variety of social and political themes, critically. In addition to expanding the limits and boundaries of their mediums, they have challenged traditional art-making norms and the predominant idea of the singular artist by privileging collaboration and incorporating a range of perspective and skill sets into their practices

In addition to the collectives we have looked at, other key artist groups have made significant contributions in a variety of ways, ranging from The Otolith Group’s essayistic film installations to Thukral and Tagra’s work that considers social issues across nearly every imaginable medium, from games to non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Navigating through the works of Indian artist collectives, this Topic engages with a number of different artists and their shared goals. We recommend the following articles for you in case you wish to learn in more detail.

Further Readings