Working with Tradition: Forms and Philosophies

As we’ve seen so far, Indian artists have engaged with the past in varied manners throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and into the present. Some of these have included replicating or appropriating imagery from historic works and mythologies, as well as devising visual strategies to bring together the past and present. Let’s now explore how modern and contemporary artists also access and respond to age-old traditions in relation to early knowledge systems, materials and processes.

The Tradition of Tantra

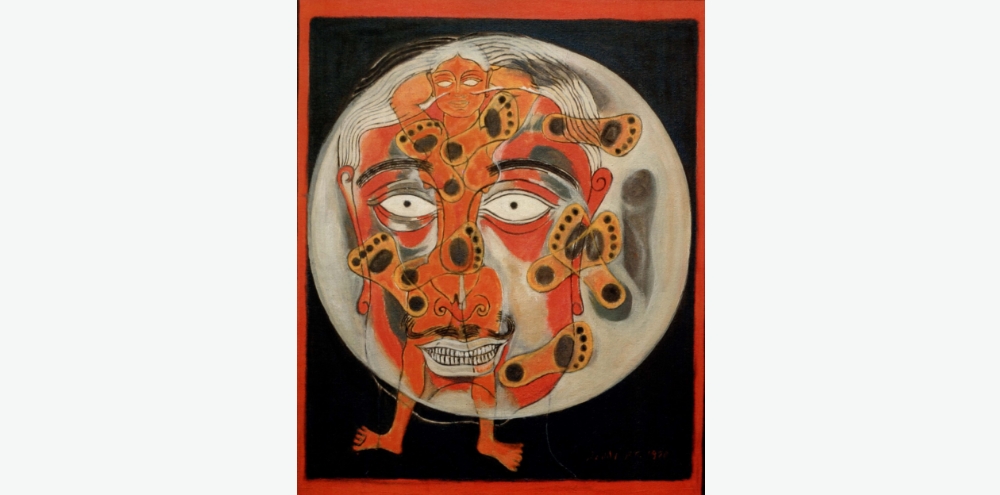

Looking through the images in the carousel above, the minimalist aesthetics of lines, colours and forms might not immediately evoke explicit associations with traditional Indian art. Yet, it is worth noting that these representations draw heavily from historical paintings associated with tantra, an esoteric tradition that originated in the Indian subcontinent around the 6th century and developed from practices of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

Tantric paintings evolved from handwritten treatises that eventually inspired a complex iconography of signs and symbols that are used in devotional and meditative practices. In India and around the world, there was renewed interest in tantra in the 1960s and 1970s, in conjunction with the rise of hippie culture as well as scholarly and philosophical inquiry. This renewal also provided the conceptual and visual bases for a category of painting in India known as the Neo-Tantric movement. Let’s turn our attention to Pakala Tirumal Reddy, one of the key artists associated with the Neo-Tantric movement.

Refashioning the Yantra: PT Reddy

PT Reddy (1915–1996) was born in present-day Telangana, Southern India. He received a diploma in painting from Sir JJ School of Art in 1939 and went on to form the artists’ group called Contemporary Painters of Bombay in 1941. Notably, this was six years before the renowned Progressive Artists’ Group — which we will learn about later in the Course — was established.

Some of Reddy’s Neo-Tantric works consider historical events like the moon landing of 1970 (Image 4), bringing together abstract imagery with some narrative or representational components, while others look much like simplified geometric diagrams called yantras. One example of this is Sree (Image 5), which adapts the form of a traditional sri yantra, a mystical diagram composed of interlocking triangles representing the cosmos and the human body. In this geometric drawing, Reddy overlays two figures in union. A later work from 1979, Sree Chakra (Image 6) also presents a yantra drawing in a new way, this time without human forms. In both of these works, the artist has taken an existing tantric form and fashioned it in his own manner.

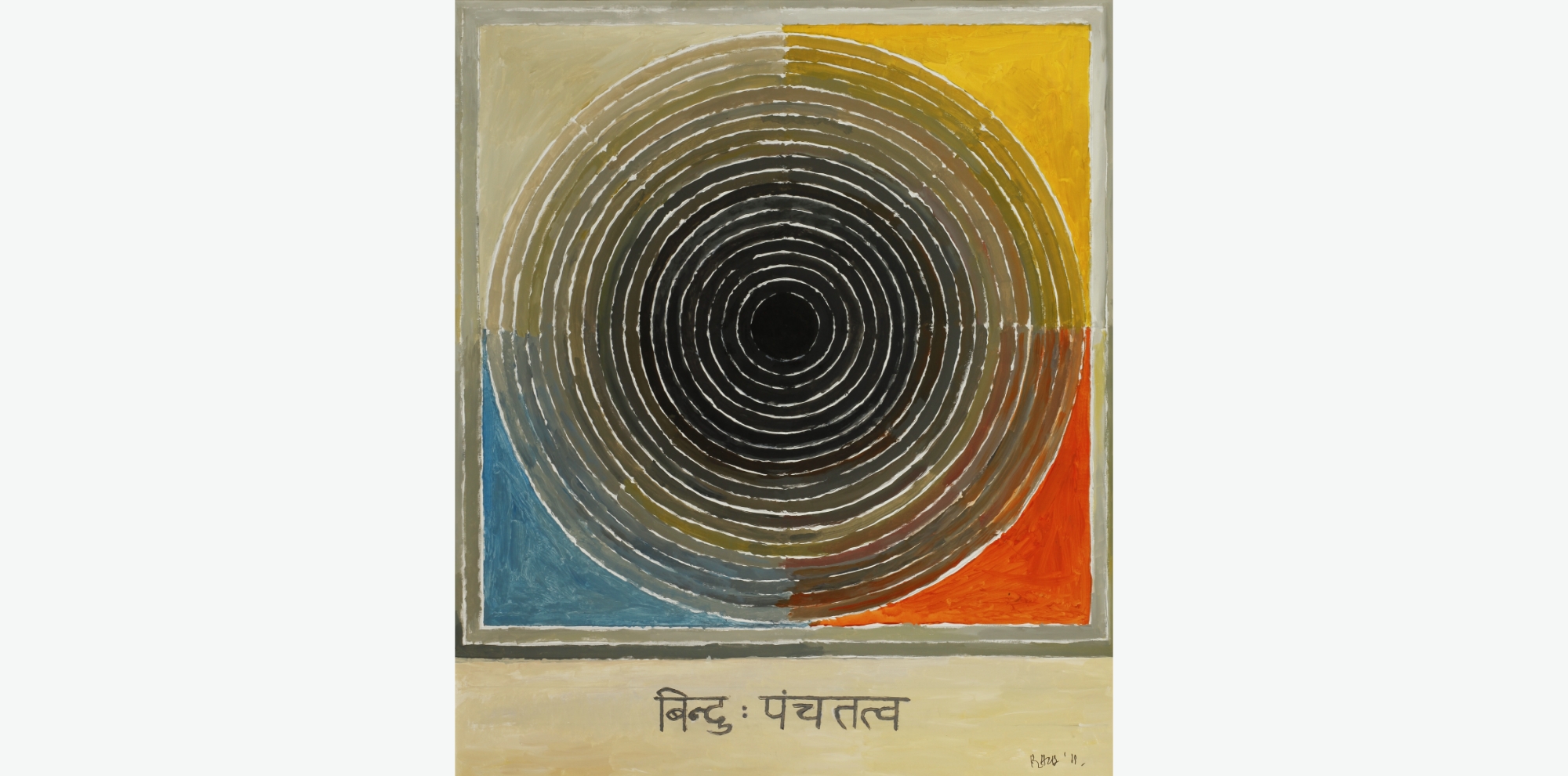

Let’s now briefly turn to Sayed Haider Raza’s ‘bindu paintings’, which can be read using similar tools.

Creation and Consciousness: SH Raza

SH Raza (1922–2016) was a founding member of the Progressive Artists’ Group. He moved from India to France in 1950 but had become restless in his work by the late 1970s. On his trips to India, he began to seek his heritage, and in the process, found the bindu, which means a ‘point’ or ‘dot’ in Sanskrit. It is a tantric form representing the cosmic point of creation and a source of consciousness, and would become a hallmark of his work for the rest of his life. Raza’s series of bindu paintings are centred on a circular black void, an abstract form that evokes the ancient Indian philosophical idea of shunya, or ‘nothingness’. As with Reddy’s works, the pared-down geometry of Raza’s paintings adopts a modern visual language of abstraction even as they are firmly rooted in Indian philosophy.

While tantra as well as other ancient religious and philosophical concepts from India continue to inspire artistic practices in the country as well as in other parts of the world, let’s turn our attention to another perspective on early traditions and explore how artists reckon with it.

India has a rich heritage of creative practices spanning stone sculpture, ceramics and manuscript paintings, among others, which predate the styles of art taught at formal art schools established in the 19th and 20th centuries. While these traditions are typically intergenerational and community-based, several modern and contemporary artists have immersed themselves within these communities, trained in their practices and developed a knowledge of their histories. In many instances, they have also adapted these traditions to create their own innovative styles. The contemporary artist Desmond Lazaro (b. 1968) is exemplary of this kind of engagement.

Working with Living Tradition: Desmond Lazaro

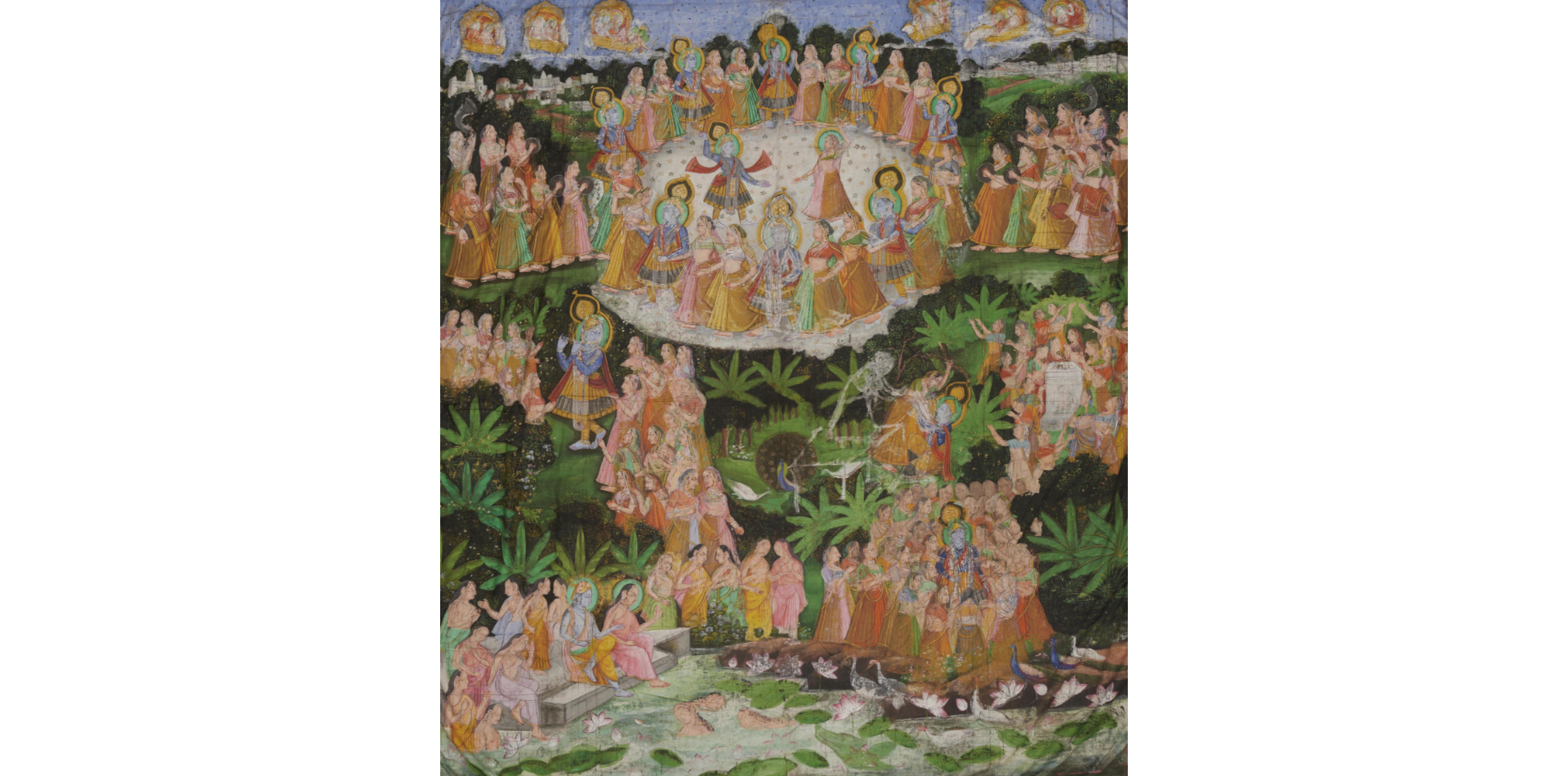

Desmond Lazaro is a British artist of Burmese and Indian heritage, currently living between Pondicherry and Melbourne, Australia. Lazaro came to India in the 1990s, to pursue his studies in Fine Art at the MS University in Baroda – about which we will learn more later in this Course. Following his degree, he spent a decade learning traditional miniature painting, an art form that dates as far back as the 7th century. He trained as an apprentice to a master artist, the late Bannu Ved Pal Sharma, in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Lazaro further specialised in surviving miniature painting workshops across Rajasthan for his PhD, focusing on pichwais, a style of devotional pictures on cloth that portray the Hindu god Krishna, of the Pushtimarga sect at Nathdwara. He learned each aspect of the pichwai process, including the grinding of pigments, preparation of the cloth as the ground for the painting, and the individual contributions of the artists. In traditional settings, a different artist would work on a different part of the pichwai, and while he participated in individual steps of the process as a student and apprentice, as a contemporary artist, he performs all the roles in creating a work from start to finish.

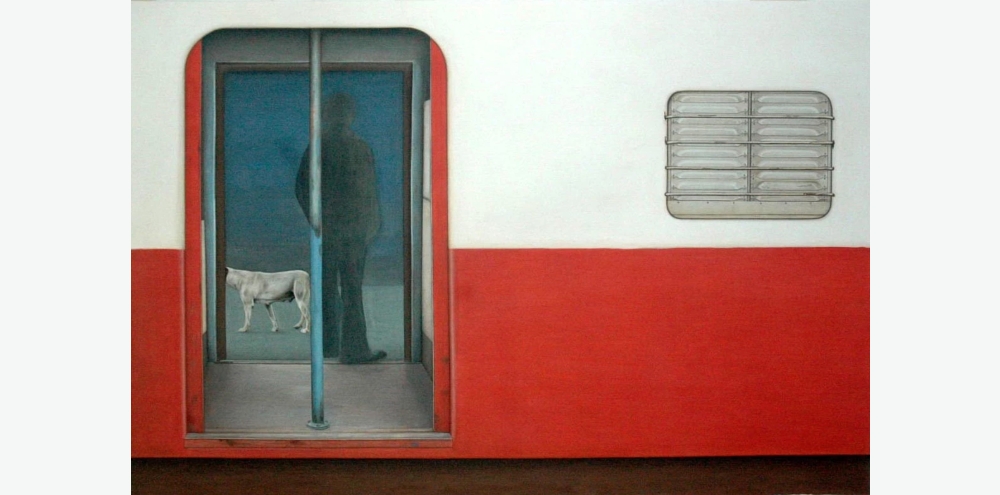

While Lazaro began his independent artistic practice with pichwais, he eventually abstracted traditional iconography from larger compositions, before moving onto secular imagery. He portrayed emblems of daily and modern life, ranging from Ambassador cars (Image 18) to scooters (Image 20) and men in train stations (Image 19). While his early work was structured around a conversation between artistic freedom and conventions, he has increasingly built his own idiom that touches on subjects ranging from his family’s history of migration to the cosmos.

As we have seen with Desmond Lazaro’s practice as well as the Neo-Tantra Movement, modern and contemporary artists who engage with historical ideas or practices have been instrumental in drawing attention to these traditions, simultaneously honouring and transforming them through new languages. At the same time, it becomes important to also challenge the relationship between artists and the community practising these traditions. In what ways might these contemporary practices also call attention to the anonymity of members of artisan communities and their labour that often remains invisible?

Inspired by traditional images, symbols and artistic styles, modern and contemporary artists have created new visual languages. If this Topic interests you, we recommend that you explore the links below in more depth.

- Tantric

- Tantrism

- Neo Tantric Art

- JJ School of Art

- SH Raza

- Bindu

- Progressive Artists' Group

- MS University

- Pichwai

- Major schools of Indian Miniature Painting

Further Readings